LOUISVILLE, Ky. (WDRB) -- The allegations were shocking.

A “good ol’ boy” who owned car lots and served as a special deputy with the Bullitt County Sheriff’s Department was, according to investigators, a major drug trafficker with connections to a Mexican drug cartel.

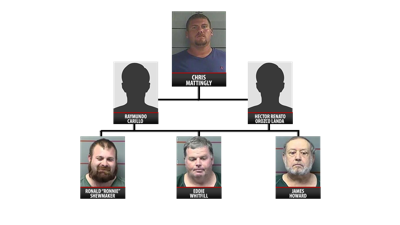

They claimed Chris Mattingly used friends and employees to sell more than a ton of marijuana and other drugs and ship hundreds of thousands of dollars across the country, while at the same time carrying a sheriff’s badge with the powers to make arrests.

In addition, Mattingly had allegedly plotted to kill a member of the sheriff department’s Drug Task Force who was investigating him, prompting 24-hour protection over several months for the officer.

All the while, prosecutors claimed, Mattingly’s neighbor aided the drug operation, even acknowledging to the FBI that he told Mattingly about a wiretap on his phone and a hidden camera watching him.

The neighbor: The then-Bullitt County Sheriff.

And at one point, when that relationship soured, Mattingly was accused of putting a contract out on the sheriff.

But in the end, after several arrests and years of a joint federal-state investigation, the government seemingly has little to show for its effort.

Facing a possible life sentence, Mattingly was cut what one attorney called “the deal of a lifetime,” serving three years in prison – mostly time served before he pleaded guilty. He is already out and was allowed to keep his property and business, despite testimony tying both to drug trafficking – thousands of dollars and several weapons were seized.

Former Sheriff Dave Greenwell was acquitted at trial this month. He was facing a minimum of ten years in prison for obstruction and aiding the operation. And several others accused of involvement in the drug ring either cut deals that called for no prison time or were never even charged.

Leonard Mattingly, Chris’ father, for example, was also accused of being caught on a wire talking about killing police officers, and trial testimony indicated he knew about the drug operation. Mattingly, also formerly a Bullitt Sheriff Department special deputy, was never charged.

Special deputies are appointed by the sheriff and have the same powers as a regular deputy, with some exceptions, such as not being allowed to make arrests in domestic violence cases.

James Alberico, an employee of Chris Mattingly’s, admitted selling drugs for Mattingly and helped load and hide money inside vehicles. He was not charged after agreeing to testify. Ronnie Shewmaker, a Shepherdsville man who said he was working for Mattingly when he was pulled over in California with $420,000 in cash, which was seized, was given probation.

Another man arrested on multiple drug charges, Eddie Whitfill – who Alberico testified was involved in drug deals – was also given probation. And James Howard, who was among the initial five men indicted, had his case dismissed. Another man from Mexico who was indicted was never caught.

The results of the case are all the more surprising when you consider federal prosecutors win more than 90 percent of their cases.

So what went wrong?

The U.S. Attorney’s office declined to make anyone available to discuss the cases and issued only a short statement saying prosecutors will “aggressively investigate and prosecute public corruption in the Western District of Kentucky.”

Defense attorneys and others with knowledge of the wide-spread investigation say prosecutors relied too much on a shaky investigation by Bullitt County investigators and questionable wiretap evidence from an agency in another state that possibly wouldn’t survive an appeal.

The investigation into Mattingly started in December 2013 when informants told a Bullitt detective that Mattingly was the leader of an extensive drug organization with ties to Mexican cartels. His name also surfaced more than 2,200 miles away on wiretap investigators had on a drug cartel member in Riverside, California.

And Shewmaker told investigators he worked for Mattingly when he was pulled over with more than $400,000 hidden in secret compartments of a vehicle registered to Mattingly Auto Sales.

After his arrest in 2015, a judge ruled Mattingly was a “real threat” to law enforcement for allegedly threatening to kill Capt. Mike Halbleib of the Drug Task Force. The judge ordered him to remain in custody prior to his trial.

While he faced a possible life sentence, Mattingly was given a plea deal in November 2016 and was later sentenced to three years in prison and a $10,000 fine, on the condition he agree to work with prosecutors.

Defense attorney Scott C. Cox, who represented Greenwell, said in retrospect, Mattingly’s plea deal was lenient, but that federal prosecutors were trying to root out public corruption.

“In this case, they gave (Mattingly) a tremendous break,” Cox said. “And there were other people they didn’t charge who were involved in drug trafficking. And there were others who were probated. But that’s a decision they make.”

The plea deal with Mattingly, and others, was in large part a gambit to convict Greenwell on obstructing an investigation and aiding Mattingly’s drug enterprise.

Mattingly, as part of his plea deal, testified earlier this month that Greenwell tipped him off about the wire taps and about a pole camera that was watching him at his car business.

But Mattingly already knew he was under investigation before Greenwell told him anything, Cox said, adding that Bullitt law enforcement repeatedly told him he was going to be arrested and was being watched.

And Cox said the jury apparently believed Greenwell when he told the FBI he provided information to Mattingly in an effort to “play good cop” and get him to provide more details, while at the same time staying in good graces with the Mattingly family to keep his family safe.

“He was solely interested in seeing these men brought to justice,” Cox said of Greenwell.

In addition, Cox said the investigation of Greenwell was “very political,” creating a dysfunctional investigation by the Bullitt County Sheriff’s Department.

For example, former Det. Lynn Hunt was overheard on a wiretap telling Mattingly about his property being searched, complaining to supervisors about the investigation and later recommending to Mattingly that he sue the department.

Hunt was investigated and later fired for her conduct and connection “with a known target of a federal investigation,” according to court documents.

“The office was widely divided on the correct way to proceed against Chris Mattingly, ranging from being very aggressive with him, to playing good cop, to telling him he should sue the department,” Cox said.

The Bullitt County Sheriff’s Department declined to comment for this article.

Asked if Mattingly was a danger to the community, Cox said he listened to the wiretap of Mattingly and his dad joking about killing police and is grateful he was convicted of a felony and is not allowed to carry a firearm.

In one recorded conversation from 2015, Leonard Mattingly said he would “blow their ***** brains out,” talking about law enforcement and say it was self-defense, according to court records. And when he asked his son what police would do, Chris Mattingly said “nothing if they’re dead.”

And Rob Eggert, another attorney for Greenwell, said there was ample evidence presented that Mattingly was a threat – arguing in court that he got the “deal of a lifetime.”

“We certainly argued that he was dangerous,” Eggert said in an interview. “There seemed to be considerable, strong evidence that he is a dangerous person.”

But Mattingly’s attorney, Brian Butler, disagreed, saying that Mattingly never threatened anyone and challenged the allegation that he was a drug kingpin. Instead, he claims zealous law enforcement in Bullitt County were focused on getting Mattingly, and oversold the case to federal prosecutors.

“He was never some international drug conspirator,” Butler said. “He distributed marijuana for a short period of time in Bullitt County and ultimately was caught and pleaded guilty. … There’s hundreds of people selling drugs illegally in this state and other states everyday.”

He said the wiretap conversations were misinterpreted and when prosecutors eventually delved into the recordings, they understood the case was not what it initially seemed.

Butler said Mattingly and his father were talking about unfair harassment by law enforcement and discussed suing police and when the entire recordings are taken in context, “there was no threat.”

Butler tried to get a judge to throw out the wiretaps, arguing they were improperly approved and that a judge in Riverside County, Calif., had authorized an “astronomical” amount of wiretaps in 2014, using “boilerplate” language and without prosecutors justifying why lesser measures weren’t taken.

While a judge overruled the request, Butler believes there was a good chance any conviction would be overturned by an appellate court because of the problematic wiretaps.

“I think all of those factors played in to the result,” he said.

As for whether the Mattingly family is a danger, Butler said Leonard Mattingly is a “salt of the earth person” who was never charged and that while Chris admittedly sold marijuana, “he’s never hurt anybody or been charged with any assault or violence.”

“He’s just a regular guy,” Butler said. “Sometimes … what we all think (at the beginning of a case) and then what ultimately plays out are not the same.”

Butler said Mattingly was harassed by Bullitt County law enforcement and constantly pulled over. He was repeatedly searched, arrested and threatened, Butler said.

At one point, Butler said he and his co-council, Alex Dathorne, had to talk Mattingly out of filing a lawsuit against the Bullitt sheriff’s department.

“I give (prosecutors) all the credit in the world for continuing to look at this case and saying, ‘Hey, what we were initially told by law enforcement may be was misinterpreted by somebody and there’s just not evidence of a threat there,’” Butler said. “The government did the right thing. … At the end of the day, that’s what the justice system is supposed to be about. Prosecutors are supposed to do what’s just.”

Greenwell, who was in law enforcement for 27 years and served six as sheriff, said he is happy to have his life back and has no intention of running for office again.

“If they can do it to you once, they can do it to you twice,” he said in an interview after the trial.

Copyright 2018 WDRB Media. All rights reserved.