LOUISVILLE, Ky. (WDRB) -- If you had to choose a person who has most shaped the landscape of Louisville, it would be hard to argue against David Jones Sr.

He was the co-founder and longtime CEO of Humana Inc., the only Fortune 500 company headquartered in Kentucky. He had a hand in — or was the driving force behind — a number of civic projects: not only Humana's stately, granite headquarters building at 500 W. Main St. but the Kentucky Center for the Arts, the Ohio River Bridges Project and the Parklands of Floyds Fork, among others.

Jones left one project unfinished before his death in 2019 at age 88: an autobiography that he had been working on since 2016.

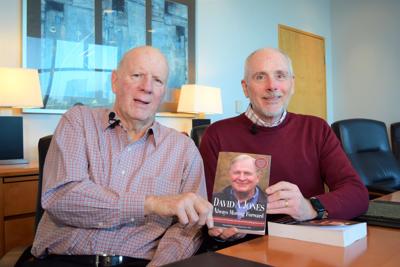

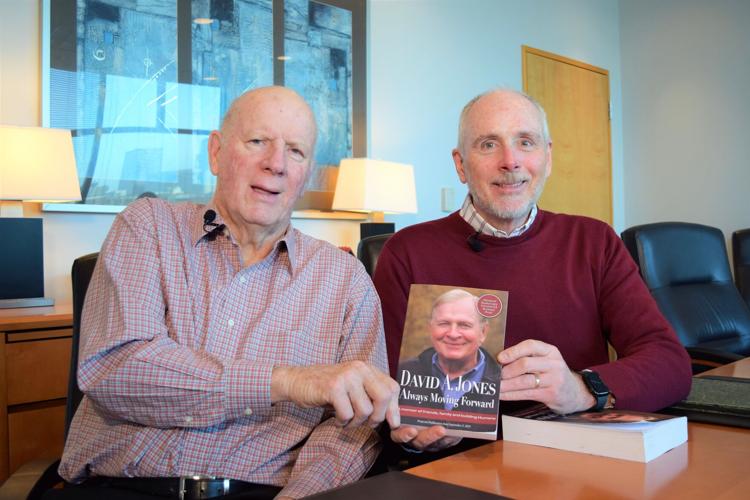

Thanks to Jones' eldest son, venture capitalist and former Humana board member David Jones Jr., and Louisville author Bob Hill, Jones' book, "Always Moving Forward," will be published by Old Stone Press nearly four years after his death Oct. 10.

As he succumbed to multiple myeloma, Jones gave his son one "last tasking" — to ensure that his manuscript was not lost to history, Jones Jr. said.

"He didn't care whether it was published commercially or anything like that but he wanted it to be finished for his family and his friends," Jones Jr. said. "His view in those last couple of months was, he'd had a great adventure. He loved his life. He was proud of what he accomplished but he wasn't hung up on it. He knew he couldn't take it with him."

Hill, a retired Courier-Journal columnist and author of eight books, conducted two dozen interviews to aid Jones' research, helped Jones structure the book and helped "whip" the manuscript into shape for publication following Jones' death, said Hill and Jones Jr.

Hill described himself as a partner — but not a ghostwriter — in the effort.

"The final product was all David's work," Hill said. "It wasn't mine."

While the book's jacket uses the words "autobiography" and "memoir," the book is more accurately described as the former.

Jones narrates the events of his life largely in chronological order, beginning with an anecdote about his mother pulling a wagon loaded with books from the Parkland Library 1.5 miles to Jones' boyhood home in west Louisville's California neighborhood in the 1930s.

It ends with Jones' pursuits in the decade following his retirement from Humana in 2005, such as the 4,000-acre Parklands project in southeastern Jefferson County, which was spearheaded by Jones' son, Dan, but supported by the elder Jones.

The title, "Always Moving Forward," is not Jones' own phrase but a synthesis of his approach to life, according to Jones Jr. and Hill. Jones was always looking ahead, an instinct that spurred him to start a nursing home company in the 1960s, to steer it into hospitals in the 1970s and to insurance in the 1990s.

"He often joked about the founding of Humana," Jones Jr. said. "You know, the market research was talking to one guy."

The "one guy" was a client of Jones when he first started practicing law in Louisville in the late 1950s. Jones was curious how his client, whom he had known since they attended Male High School together, could afford such a big house. The answer: He was in the nursing home business.

"So Dad runs back to the law firm, and says, 'Wendell, we've got to build a nursing home," Jones Jr. said, referring to Wendell Cherry, Humana's co-founder and Jones' best friend, who died of cancer at 55 in 1991. "... He said, 'Thinking is really good, but action is what changes things.'"

Jones' aversion to dwelling on the past may have served him well in business. The readers of his autobiography, however, may be left wanting for his lack of introspection and reflection at certain key moments.

The book covers much territory — especially at the height of Jones' reign at Humana in the late 1990s and early 2000s — by relating what Jones was quoted as saying in the newspaper or what was said about him at the time, without offering Jones' own thoughts on the developments.

For example, Jones' initial successor as CEO of Humana, Gregory Wolf, resigned after a rocky 20-month tenure in 1999. Jones relates that a stock analyst at the time had described Wolf's abrupt departure in 1999 as "probably part of a move by me to put the company back on track quickly."

Whether that third-party description of Jones' mindset some 20 years ago was accurate, Jones leaves the reader to wonder.

Jones' book is, above all, a testament to his love for his hometown and all he did to champion Louisville as a civic leader and philanthropist.

As he notes, the trappings of Humana's ascendance in the 1980s — the Humana building, the Humana Festival of New American Plays at Actors Theatre (RIP), the Kentucky Center for the Performing Arts — "had given the city and the company a glow it never had."

But Jones' aversion to reflection is perhaps most glaring in his passing treatment of two instances in which the crown jewel, Humana, was almost sold. Jones was firmly in the driver's seat during one of these periods, a failed merger with United Healthcare in the 1990s.

Jones relates newspaper stories about the anxiety that the prospect of losing Humana created in Louisville, perhaps the loss of thousands of jobs and "a big void in city leadership." The thrust of the book would imply that Jones must have had some complicated feelings about this, perhaps difficulty balancing his love for his hometown and his duty to maximize Humana's value for its disparate shareholders.

Jones offers no such reflections, however. He does inform the reader that, following the dissolution of United Healthcare merger, one constituency was disappointed: the investment bankers.

"They make a lot of money on these deals," he said.

Humana's second brush with corporate absorption came in 2015 when the company agreed to sell itself to rival insurer Aetna. That deal fell apart in 2017. While Jones was long gone from the boardroom for that episode, the book dispatches it with one sentence: "And other merger ideas came along after I retired, like the failed combination with Aetna in 2017."

Hill and Jones Jr. explained Jones' reluctance as partly customary business politeness — it's obvious when resignations are really firings, for example — and partly Jones' preference.

"It was just the nature of his personality," Hill said. "I guess he just kept that inside himself — more so, not wanting to share."

Hill added that Jones' declining health in 2019 curtailed discussions about how to revise the manuscript. Hill didn't see Jones in the final six to eight months of his life, Hill said.

"I'm just guessing that was part of the problem here, because it just kind of faded away," Hill said. "There was a finished, yet unfinished, book there that, you know, maybe something else could have come about, but I had no communication about that at the end."

Jones Jr. said it's unfortunate that his father didn't publish the book before his decline so he could participate in discussions about it.

"It would have been interesting if he'd published it while he was alive and gotten to be interviewed himself about what he thinks," Jones Jr. said. "I will just say, mostly, he didn't spend a lot of time wallowing in looking backwards at what might have been."

What the book reveals, however, is the extent of Jones' relationships in Louisville, and the importance of those local ties in Jones' success. For instance, as he relates, Humana wouldn't have existed but for a last-minute loan Jones and Cherry received from a local banker, the late Sam Klein, which allowed them to buy their third nursing home in 1963.

Jones and his brother Logan first encountered Klein when, as boys, they walked by Klein's car dealership on Broadway on their way to the YMCA. Klein, who co-owned the Bank of Louisville, would later step in to provide Jones and Cherry personal loans with little collateral in the early 1970s, allowing them to escape a period of over-extension that also could have spelled doom.

Jones was rooted in Louisville in a way that may seem quaint for a Fortune 50 CEO today. He describes using lunch hours in the 1960s and 70s to play pick-up basketball with whomever else would show up at the downtown YMCA. One of the players he befriended was the Rev. Louis Coleman, a prominent civil rights figure locally.

While "Always Moving Forward" does not aim to be a "business book," Jones offers some simple and timeless advice for those looking to replicate his success: trust the people you hire to get the job done, give them more responsibility when they succeed and, most of all, let them know they are appreciated.

Hill said was the recipient of four or five handwritten "Thank You" notes from Jones during the book project. Jones sent "thousands" of handwritten notes to people he worked and interacted with over the decades, Hill said. Many of Hill's interviews subjects kept those notes.

"That meant so much to people, to have the written word, as well as the feeling, of working with David," Hill said.