LOUISVLLE, Ky. (WDRB) -- Jefferson County Public Schools will begin a new chapter of its storied transportation history Aug. 8 when nearly 100,000 kids return to class across Louisville.

For the last 70 years, Kentucky's largest school district's transportation plan has taken many forms. And on more than one occasion, the plan has made statewide and even national headlines. Decisions have been protested and celebrated, the results of everything from U.S. Supreme Court decisions to racial strife.

This is a brief summary of the many chapters of JCPS' busing history:

1954: Brown v. the Board of Education

In the mid 20th century, U.S. Supreme Court unanimously ruled in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, that separating children in public schools on the basis of race was unconstitutional and a violation of the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment.

At this point, JCPS was separate from the now-defunct Louisville Public Schools system. Unlike other schools in the south, such as Little Rock, Arkansas, Louisville Public Schools' integration efforts were celebrated and met with little resistance. According to a 1956 newsletter posted by the JCPS Archives and Records Center, then-LPS Superintendent Omer Carmichael traveled to Washington to meet with President Dwight D. Eisenhower, who praised the school district's preparation and implementation of desegregation.

However, as the 1950s and 60s carried on, white families reportedly began leaving the city school district for the county, and efforts to desegregate were eroding within LPS.

Early 1970s: More federal orders to desegregate

The trend of growing suburbs was not isolated to Louisville, and, as a result, activists argued schools were bound to either become re-segregated or never fully achieve segregation in the first place.

A 1971 Supreme Court decision — Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education — ruled it was acceptable for districts to achieve racial balance in schools through busing.

Around this time, at the local level, the idea to merge LPS and JCPS to achieve desegregation arose. Eventually, Kentucky civil rights groups filed a lawsuit requesting the court to order schools to desegregate, and the Kentucky Commission on Human Rights requested the city, county and Anchorage Public Schools to merge.

By the mid 1970s, a decision was made to merge the city and county schools. Anchorage Public Schools argued its way out of the merger and remains an independent school district in eastern Jefferson County.

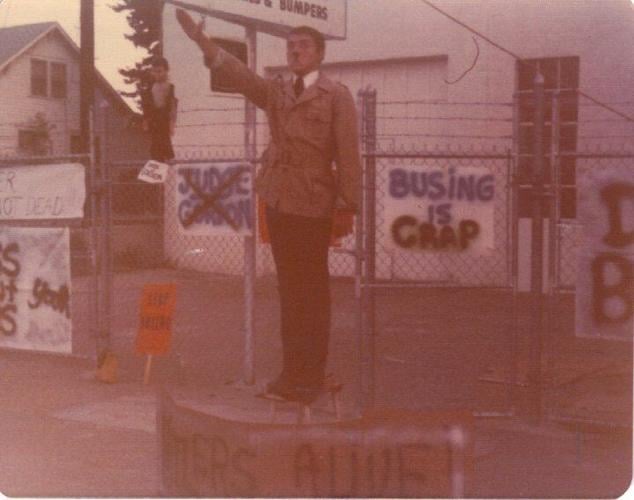

1975: As districts merge, protests ensue

After a series of court challenges, the decision to merge the city and suburban districts was upheld, and JCPS — as we know it today — was created. But it all didn't happen without protests.

To ensure desegregation, the merger required Black and white students to be bused, mandating student bodies be between 12-35% Black. Therefore, a court-imposed busing plan was ordered by Sixth U.S. District Judge James Gordon.

The fallout was drastic for some students. For example, Edward Pennix, who was 8 years old at the time and about to enter the second grade, started his education within LPS at the original Brandeis Elementary School in west Louisville. The school was across the street from where he lived. But in the fall of 1975, Pennix boarded a bus full of Black students from his neighborhood and was bused to Okolona Elementary School 10 miles from home.

The original order mandated Black students be bused for more years than white students.

"It was forced. Everybody got bused at some point in time," Pennix said. "For the most part, it was an all-white school. ... They didn't want us there."

Busing Black students to mostly white schools, and vice versa, wasn't met with the same acceptance as the desegregation efforts of the 50s. Protests and riots took over streets of Jefferson County, creating a contentious bus ride to school for Pennix. Nearly 50 years later, he recalled hundreds of people lining the streets of Preston Highway as his bus approached Okolona.

"We had the National Guard on our bus from the first day of school," he said. "Rocks were thrown at the bus."

All these years later, he still remembers the protests lasting until the winter.

"Their signs said more than what they were yelling," Pennix said. "Go home. We don't want you here. The n-word/ We had been forced to go to school, and, I mean, we had to be resilient. We weren't fighting it. We couldn't fight it."

By the late 1970s, Gordon ended the court's supervision, but the desegregation decree remained in place, and JCPS continued to bus students.

1980s-90s: Student assignment plan altered

After Pennix graduated from Central High School in the 1980s, he remembered the hostility of desegregation calmed down. But over the course of the next two decades, JCPS continuously altered its student assignment plan to further achieve racial balance.

That is why JCPS graduate Grace Rodgers — now the mother of two students — remembers being bused to a school far away from home.

"I was never able to go to any schools in that neighborhood," Rodgers said. "I was always bused outside of it."

2000s: Lawsuits strike racial quotas

A trilogy of lawsuits throughout the late 1990s and early 2000s scrapped racial quotas. The final, known as Meredith v. JCPS, made it all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, the justices ultimately ruling that race could not be the sole factor in assigning children to schools.

So JCPS changed its plan again, focusing student assignment plans instead on socio-economic factors like household income and parental education levels. Students continued to experience lengthy bus routes so the district could achieve diversity in schools.

The student assignment plan continued to be altered over the course of the next decade, often with opponents raising concern of re-segregating schools.

2020s: Two student assignment plans create transportation disaster

In 2022, JCPS again changed its student assignment plan, and Superintendent Dr. Marty Pollio called it the most significant change in 40 years.

"This will have the most positive impact on students we have in this district in decades," Pollio said at a June 2022 board meeting.

The new plan guaranteed students in the newly designated "choice-zone" — comprised of all of west and part of central and south Louisville — the opportunity to attend neighborhood schools, or a network of schools, based off a their home address. The plan streamlined a feeder system of schools for students to attend while also still offering choice to attend magnet or traditional schools.

And it eliminated forced busing for students.

The new plan took effect during the 2023-24 school year, beginning with kindergarten, sixth- and ninth-grade students. It also grandfathered in students under its previous assignment plan.

However, coupled with drastic changes to start times, a shortage of bus drivers and new routes drawn up by an out-of-state company using AI technology, the plan proved disastrous from the very first day of school.

The final student didn't get home until nearly 10 p.m. that night, and JCPS promptly canceled classes for more than a week to address the issues. The following week, the district then implemented a staggered return to ease back into the beginning of the year.

“First and foremost, I want to apologize for what happened last night,” Pollio said in a recorded message sent to JCPS families and posted on social media after the first day of school.

Admitting the first day was unacceptable and the reality JCPS would not be able to hire enough bus drivers to meet the transportation plan's need, the Jefferson County Board of Education made a contentious decision in April 2024: cut transportation for students not attending their reside and choosing to attend magnet programs/schools, traditional schools or Academies of Louisville programs.

That decision meant Rodgers, now a mother of two JCPS students, would no longer have access to transportation for her students to attend their traditional school, Greathouse-Shryock Elementary. The school is near Hikes Point, but Rodgers' family lives in the west Louisville.

Now: What's to come

While Rodgers' kids have the opportunity to attend school closer to home under the latest student assignment plan, Rodgers said it does not meet the same standards as her kids' current school.

"I want them to have access to good education," she said. "I don't want to just say 'Hey, this is close in proximity. Just go here' and I'm just throwing you wherever."

Rodgers will join other JCPS families who no longer have access to transportation and take her kids to school.

Meanwhile, JCPS hopes it can begin this school year on a better note on Aug. 8, which will mark the beginning of a new chapter for JCPS and transportation.

Related Stories:

- JCPS 'learned a lot' from last year as it works to avoid repeat of first day transportation mess

- TARC drivers making final preps to get behind the wheel of JCPS buses

- JCPS schools adjusting traffic patterns around campuses, neighborhoods

Copyright 2024 WDRB Media. All Rights Reserved.