LOUISVILLE, Ky. (WDRB) — Dave Oetken, Connie Schilffarth and Nancy O’Hearn sat side-by-side in the airy, sun-lit “conservatory” of the Galt House Hotel — the glass-encased pedestrian bridge that spans Fourth Street and connects the two hotel towers that their late father and grandfather, Al J. Schneider, built in the 1970s and 1980s.

The Schneider descendants — O’Hearn is Schneider’s oldest living child, while Oetken and Schilffarth are among his grandchildren — presented a united front with respect to the future of the Al J. Schneider Co., the hotel and office building empire their patriarch built.

After a bruising, seven-year legal battle among Schneider’s many heirs, the company will continue its 75-year history in Louisville as an independent, family-owned concern, they said.

“And I hope my great-grandchildren are working here in the hotel,” O’Hearn said.

Not all of Schneider’s descendants will carry on the famed Louisville developer’s legacy, however. Notably absent from WDRB’s interview last week was the person who created the very lounge in which the family members sat: O’Hearn’s younger sister, Mary Moseley.

Moseley, Schneider’s fourth-born child, led the company for 15 years after her father’s death in 2001. In 2016, she was ousted as CEO — or she retired, depending on whom you ask — as long-simmering family tensions finally boiled over.

From the archives: ‘We weren't a family anymore' | The inside story of the dispute that broke the family behind Louisville's Galt House (published 2019)

The fight was prompted in part by Moseley’s ill-fated effort to sell the company’s crown-jewel: the 1,300-room Galt House, the largest hotel in Kentucky, for about $135 million. When the family dispute went public, the deal fell apart.

The dispute pitted Moseley, 73, and her sister Dawn Hitron, 69, against O’Hearn, 77, and her sister Christe Coe, 71. It also involved several family members from the third generation of the Schneider clan, such as Oetken. (Schneider’s oldest children — Joy Oetken and Al J. “Kayo” Schneider Jr. — died in 2003 and 2005, respectively.)

After seven years, dozens of depositions, several private mediations and millions of dollars in legal fees, Schneider’s four surviving daughters finally reached a truce this year — though not a reconciliation.

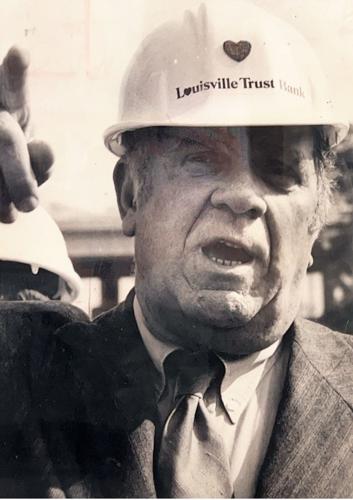

A photo of the late Al J. Schneider hangs in the lobby of the Al J. Schneider Co. office.

The Schneider daughters and the company announced the resolution in a brief statement last month, though they disclosed no details about the terms of the agreement.

WDRB News has learned it involves a series of payments to Moseley and Hitron — as well as three other Schneider descendants aligned with them — in exchange for their stakes in the company.

It’s unclear how much Moseley and Hitron are set to receive for walking away. In 2019, they demanded about $45 million each for their shares based on a private valuation that pegged the company’s total enterprise value at about $284 million, according to WDRB’s analysis.

Aside from the Galt House overlooking the Ohio River, the Schneider Co. owns the adjacent office towers known as Riverfront Plaza and Waterfront Plaza, as well as the Embassy Suites hotel at 501 S. Fourth Street and the Crowne Plaza Louisville Airport hotel.

The family members now at the helm — a faction that includes the majority of Schneider’s descendants — said they’re carrying on Schneider’s wish for his business to remain in the family.

Asked if the company is still considering selling any of its assets, Oetken, Schilffarth and O’Hearn answered in unison: “No.”

“This is one of the larger family-owned businesses in Louisville, and we’re committed to the community. And so we plan on being a part of the community (and) investing more in the community,” said Oetken, chairman of the Schneider Co.’s board of directors.

O’Hearn said the resolution of the dispute with her sisters is “such a relief.”

“The family can get back together now and go forward where (before) we were just stymied,” O’Hearn said.

When the dispute began, Louisville was in the early years of a bourbon-tourism boom that has resulted in dozens of new hotels. The $300 million Omni Hotel, for example, was completed in 2018 when the Schneider offspring were still in the thick of their fight.

Despite the battle, the company -- now led by CEO Scott Shoenberger, a hospitality veteran and non-family member -- financed an $80 million renovation of the aging Galt House.

Even in the new, more competitive landscape, the company’s prospects are bright, according to Oetken.

He said the Schneider Co. set records in revenue and hotel occupancy in 2022, though he declined to share specific figures. The company had about $100 million in revenue in 2018, according to documents produced as part of the litigation.

'A lot personalities, a lot of resentment'

Dawn Hitron, 69, and Mary Moseley, 73, are among the late Al J. Schneider's six children. They posed in Moseley's living room on March 4, 2023.

The complexity of the sprawling legal battle can be reduced to an old-fashioned family rift — one that was well documented through dozens of emails and depositions.

The faction that now controls the company felt Moseley shut them out and abused her position, siphoning company money to her husband and son. Some — notably, O’Hearn — never accepted Moseley’s claim that her father had chosen her to be his successor in the first place.

In their narrative, Moseley rushed to sell off the company, starting with the Galt House, for crumbs because she couldn’t face the inevitability of losing control.

Moseley, for her part, felt saddled with deep animosities from some siblings, in-laws, nieces and nephews as soon as her father unilaterally designated her as his successor around 2000. Over the years, she tried to bring them into the company’s governance, but never succeeded, she said.

“Family businesses are very difficult — a lot of personalities, a lot of resentment, a lot of jealousies,” Moseley told WDRB News in an interview last week. “You’re always a sister, an aunt, a cousin. You’re not the CEO to them, no matter what you do.”

To Moseley, platitudes about keeping a family business intact ring hollow, as many of Schneider’s descendants agitated for years for more money out of the company, even if it meant selling assets.

Moseley said she is proud of steering the company from a $50 million valuation when she took over only months before the 9/11 terrorist attacks to about $250 million when she left.

Since 2016, Moseley and Hitron have aimed to split from their family by selling their shares to the company based on a fair valuation of the total enterprise — thus, their demand for $45 million each in 2019.

Among many issues in the legal dispute was whether the company had to honor a 2012 agreement allowing any shareholder to cash out upon request, which could force a sale of the whole company.

Moseley and Hitron seemed to have won the debate with a Jefferson Circuit Court judge’s ruling in their favor in 2019. But in 2021, the Kentucky Court of Appeals said the issue wasn’t settled after all.

The 2021 decision meant many more months, perhaps years, of litigation, prompting the company and family back to negotiations.

'We fought a good fight on his behalf'

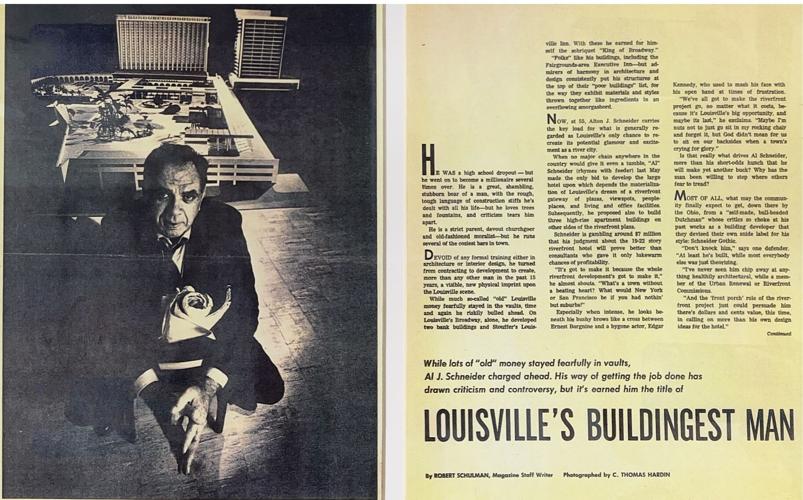

A magazine profile of Al J. Schneider hangs in the lobby of the Al J. Schneider Co. office.

Not surprisingly, the two factions disagree on a fundamental question: whether the seven-year fight was worth it.

“I don't think it was Mr. Schneider’s intention for what he had to be liquidated ... He wanted it to go on and (to) go on as long as possible,” Oetken told WDRB News. “So, I think we fought a good fight on his behalf. And we did what he wanted.”

O’Hearn added: “It was worth it to have the control back in the family’s hands, and not (in the hands) of one individual … very well worth it.”

Moseley, however, said the dispute “could have all been resolved with a meeting,” which her family members refused to have.

“What a great way to spend a lot of money,” she said. “I’m glad it’s over.”