LOUISVILLE, Ky. (WDRB) -- They came and celebrated one more time on the Bellarmine University campus Monday. They praised a basketball team that had won the ASUN Championship, an NCAA Division I conference tournament in only its second year of reclassification.

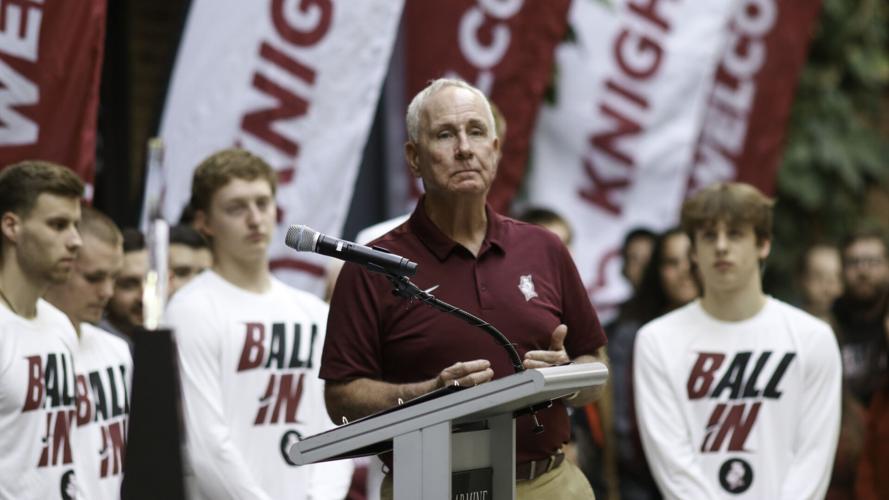

The pep band played. There were speeches from players, from head basketball coach Scott Davenport and President Dr. Susan Donovan. There was a balloon drop.

But it all still felt empty. Selection Sunday came and went, and all Bellarmine had to show for it was the briefest of mentions on the CBS selection show telecast, explaining why the ASUN's tournament champion wouldn't be playing in the NCAA Tournament.

Appeals to the NCAA to make an exception and allow the only program in 25 years to win a conference tournament while reclassifying fell on deaf ears. Bellarmine understood it could not play in the NCAA Tournament. It had hoped to persuade the NCAA to acknowledge its special circumstance and allow it to play in the NIT. It got nothing.

Davenport even sent a lengthy email to the NCAA. At last check, it hadn't responded. So the Knights ended their season. They won't spend the $50,000-plus to play in the College Basketball Invitational, a tournament they played in a year ago, beating Army, before losing in the semifinals to eventual champion Pepperdine.

The final image of this team will be on a packed Freedom Hall court, celebrating a banner season that few outside the locker room expected.

Bellarmine athletics director Scott Wiegandt with the ASUN Tournament trophy.

Davenport got texts Monday from UCLA head coach Mick Cronin, from Seton Hall's Kevin Willard, from assistant coaches at Gonzaga and former players all over the country.

The outpouring has been impressive. A story in The New York Times. Prominent mention on Pardon the Interruption. Everyone seems to recognize the novelty and rarity of what this Bellarmine team managed to do last week — except the NCAA.

And that's a painful thing for these players and their coaches.

"I just hate it for the players," Davenport said. "I got a text from Mick Cronin, who is getting ready to play in the NCAA Tournament at UCLA. And he said he knew we'd stay positive through this and said that only two teams are left standing after a win at the end of the season, the winner of the NCAA Tournament and NIT. And this year there is one more: Bellarmine. And he's right. . . . And he reminded me that for a third time in my career, my season will end on a ladder. At Ballard in Freedom Hall. A Division I national championship. And this season."

It's always the players who pay. Always. Women's basketball players learned that last season when they got to their NCAA Tournament bubble and found inadequate training facilities and the bare minimum in food and other necessities. Men's players got a big gift bag. Women's players got little. It took a national rebuke for the NCAA to even think about changing course.

I was thinking about my own NCAA experiences as a reporter.

Soon after I came to Louisville, I covered the story of Muhammad Lasege. He grew up in Lagos, Nigeria, a place where people waited in line for days for a chance to fill out paperwork to immigrate to the U.S. He was taken advantage of by a "promoter" who promised an opportunity to play college basketball in the U.S. He was taken to Russia. Practiced at gunpoint. Escaped, eventually, and wound up in Canada. With the help of a fellow Nigerian, Hakeem Olajuwon, he made it to the U.S., wound up signing with Denny Crum at Louisville.

At age 16, Lasege had signed something labeled, in Russian, a "work agreement." The NCAA decided that was a contract with an agent. A document in a language he did not speak that he signed when he was a minor. No matter. He was declared ineligible. The NCAA said he showed a clear "intent to professionalize." No, his intent was to get a college education. Rick Pitino helped him make that happen after the NCAA ended his college basketball career. He graduated, went to work. When he wanted to go to graduate school and had visa issues, Pitino suggested he use basketball to make some money. He went to Iran and played professionally to save money for graduate school. He wound up going to the prestigious Wharton School of Business. He's an executive at Exxon today.

Little thanks to the NCAA, a giant bureaucracy, for bullying a player who represented all the things it touts in its television commercials.

Bellarmine player Ethan Claycomb acknowledges the university faculty while speaking during a celebration of the school's ASUN Tournament championship.

There was Marvin Stone. The NCAA descended on him at the end of his senior year at Louisville, trying to get him to implicate a former AAU coach of some kind of violation. It went after him hard, and because he hired an attorney, Don Jackson, some of its tactics were made public. It accused him of receiving money orders and came into one meeting asking Stone to explain. He'd never seen them, he told them. Then Jackson did his own digging. He called a number on the money orders to learn that they'd been sent to another Marvin Stone, in Atlanta, a building maintenance man who was none too happy that the NCAA had obtained his private financial documents. The NCAA's case unraveled from there, and it wound up backing off but not before he'd missed several games and the season been derailed at a crucial point.

There was the NCAA super regional baseball game at Louisville in 2007 when the Cardinals were about to get to a College World Series. My then-newspaper colleague, Brian Bennett, was live blogging from the press box. The NCAA didn't like it. During the game, Louisville Athletics Director Tom Jurich got a phone call from the NCAA that it needed to kick Bennett out of the game or it would never host another baseball regional. Jurich's response, "You want him out, come do it yourself." So it did. Bennett got tossed, and I wound up pinch-hitting. And the sanctity of college sports was saved.

And here's Bellarmine. All the NCAA had to do was issue a waiver to let Bellarmine play in the NIT. No team since the NCAA has run the NIT has been in Bellarmine's situation. There might never be another team in it. Bellarmine has had a Division I lacrosse program for 17 years. It showed up in Division I men's basketball ready to play from day one. It's not going anywhere.

Instead, NCAA leadership turned its back on those players. Like it always does. Like it did in imposing any kind of penalty on a Michigan State program with a predator on the training staff. Or other examples, like the University of Texas or Ohio State, where doctors, trainers, coaches or others have been allowed to prey on students without NCAA action.

When it comes to athletes, you can almost count on the NCAA doing the wrong thing until it is made to do the right thing, usually because it has a financial interest in doing so.

On its website, the NCAA calls itself, "a member-led organization dedicated to the well-being and lifelong success of college athletes.”

The other education that students get from college sports is that quite often, organizations like the NCAA are full of it. Bellarmine players will leave with a story to tell. Just like Lasege did. Part of his entrance process at Wharton was talking about his NCAA experience.

Bellarmine players weren’t asking for a chance to play in the NCAA Tournament. They were just asking for an invitation to the next tournament down — and an invitational tournament at that. They just wanted a piece of what they had earned. Instead, they got an unfortunate education.

The organization says it is about opportunity. It is about money. Yes, it is an organization made up of members. But day to day, it is a bureaucracy that serves itself as much as it serves anyone else. It rarely sees beyond its own rulebook. It always protects its bottom line.

Today, there are cracks in its foundation. At some point, it will crumble. If it wonders why more people aren't there to mourn its loss, it can look at how it treated the little guy for so many years.

After the band and fans and students had filed out of the hall where Bellarmine celebrated its conference tournament title, the balloons still covered the floor, and Davenport walked over to his family, still grateful for the program's swift success but rankled by the lack of any response from an organization pledged to the "success of student athletes."

After a celebration of his team's ASUN Tournament championship, Bellarmine coach Scott Davenport (background center) chats with his family.

Copyright 2022 WDRB Media. All Rights Reserved.