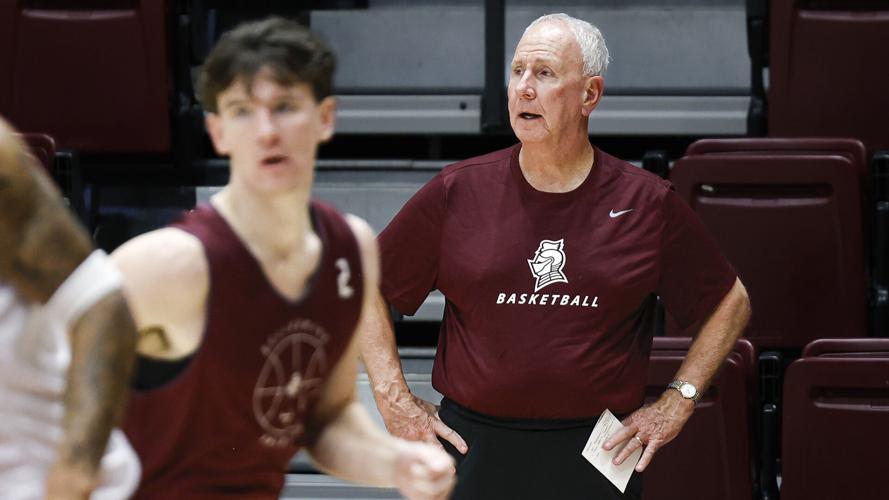

LOUISVILLE, Ky. (WDRB) -- Caring is a talent. If I heard Scott Davenport say that one time over the past 25 years, I heard him say it several hundred. Of all the coaches I've covered and the few I got to know well — and that includes some big names, like his mentors Rick Pitino and Denny Crum and his great friend Jeff Walz — nobody cared more than Scott Davenport.

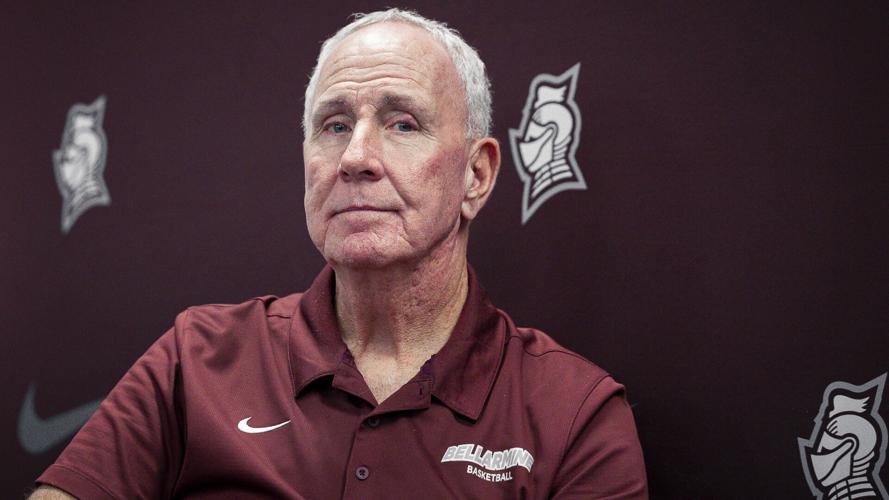

On Sunday night, Davenport, 68, told his players in an emotional team meeting at Knights Hall that he decided to retire. If you know him, and you know how much he cares, you know how hard a decision that was.

"It's Doug's turn," Davenport said in a statement announcing his decision, referencing his son, who will succeed him according to an agreement reached in 2022. "He deserves this tremendous opportunity. He's earned it. I will be forever thankful to every player, manager, coach and administrator I have worked both with and for. From attending Frayser Elementary to Southern Junior High (now Olmstead North) to Iroquois High School to the University of Louisville (two degrees plus), education has been the answer. I have been b blessed to coach 46 of my 47 years in the greatest, most passionate, knowledgeable basketball community in the world. Coaching at Ahrens High School (closed in '80), Ballard, VCU, Louisville and 20 incredible years at Bellarmine has been a blessing I will cherish forever."

He wraps his career with a collegiate record of 423-192, with an NCAA Division II National Championship and four Final Fours at that level, plus an ASUN Tournament championship at the Division I level. He was National Division II Coach of the Year in 2011, and four times was Great Lakes Valley Conference Coach of the Year.

At the high school level, he went to back-to-back state championship games and won the state title at Ballard High School before beginning a nine-year stint as an assistant to Crum and then Pitino at Louisville. Davenport was inducted into the Kentucky Athletic Hall of Fame in 2016.

All of that, however, only begins to tell his story.

Davenport took over at Bellarmine as head coach in 2005, right after working as an assistant to Pitino's first Final Four team at Louisville. If anyone ever were born to coach a program, Davenport was born for the job at the Catholic university in Louisville's Belknap neighborhood.

After three seasons of .500 basketball or thereabouts, he had the Knights in the NCAA Division II Sweet 16 in his fourth year and would have them in the Big Dance in each of the next nine seasons, including an NCAA Division II championship in 2010-11 and four trips to the Division II Final Four.

He then ushered the Knights into their NCAA Division I era, going 14-8 in their first season, 10-3 in the ASUN for a second-place finish and a trip to the College Basketball Invitational postseason tournament.

The next year, Bellarmine would go 20-13 overall, 11-5 in the ASUN and win the ASUN Tournament, qualifying for NCAA Tournament competition in its second Division I season, had it not been barred from competing by NCAA reclassification rules.

Bellarmine coach Scott Davenport cuts down the net after his team won the ASUN Tournament championship in Freedom Hall in 2022.

That reclassification process took a toll on the program. As did COVID. And finally, the advent of Name, Image and Likeness compensation and the transfer portal. In the final week before the portal window closed before what would be his last season, three of Bellarmine's best players went elsewhere for more lucrative financial offers. Davenport's final season, a record of 5-26, 2-16 in conference play, is not how he wanted to go out.

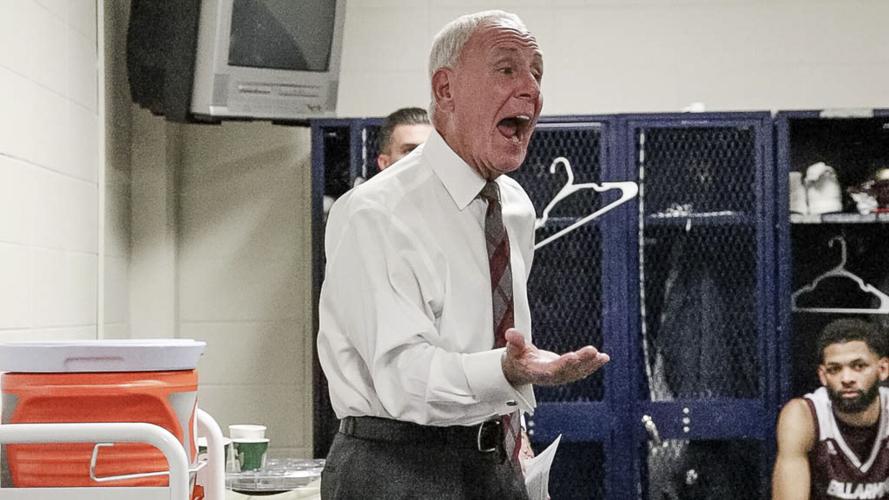

But the team gave him two home wins in his final two games in Knights Hall, a 94-68 trouncing of Austin Peay, and then an 80-74 upset of an EKU team that had won eight straight games coming into the matchup. After a long and frustrating season, his players were still engaged, still playing hard, still playing with pride. It was a rare thing to see.

After that game, Davenport said, "I put 20 years of my life in producing quality young people, and when the portal, with a day and a half to go, devastates your team, you've got to make a decision. . . . With a day-and-a-half (left in the portal window), who's left in it are not admirable people. And I was not going to sacrifice 20 years of investing in this program and this university. We took good people."

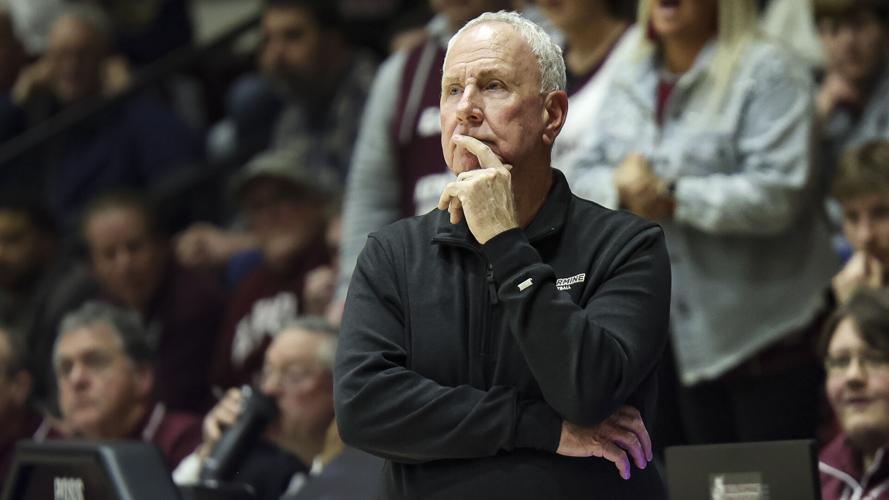

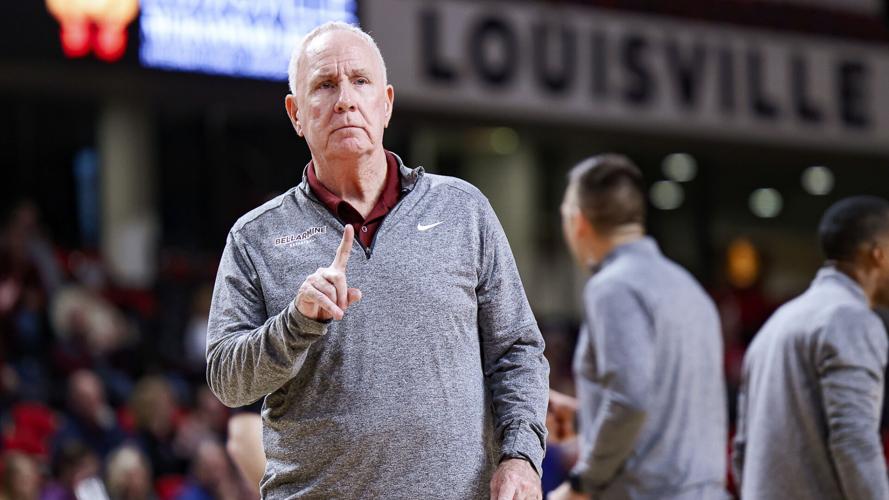

Davenport is coming off of 20 years at Bellarmine.

Davenport's Louisville Legacy

And he leaves a strong legacy, not just at Bellarmine, but all over Louisville.

Davenport got hooked on basketball when his father built him a basketball goal in the back yard. His dad wouldn't get to see the result of that one selfless act. He died when Davenport was in the fourth grade. Life wasn't exactly easy for Davenport. In junior high, his coach liked for players to wear a necktie on game days. Davenport didn't have a tie, and once his mother got him one, he didn't have a father to help him tie it. So, on game days, he'd go to the coach's office in the morning, and the coach would tie his necktie, so he could look like the other players.

Seldom does Davenport tie a necktie today that he doesn't remember the difference that coach made to him. Nor does he forget his high school coach at Iroquois, who gave him odd jobs, including cleaning the football stadium by hand after games, to make extra money to help out at home.

Scott Davenport on the Bellarmine team bus on its way to a road game at Notre Dame.

Davenport was just a student at the University of Louisville hanging out at Crawford Gym when a group of faculty members playing needed one more player. He hit the court in his Converse and jeans and T-shirt. After the game, one of the faculty asked him if he'd played. He said he had. The man told him he should come out for the JV team, to go see Judy Cowgill in the basketball office and talk to coach Jerry Jones.

That man was Bill Olsen, then an assistant to Crum.

"That day," Davenport said, "changed my life forever."

All along the way, Davenport can trace a line of coaches who stepped in to lift him up, help him along and chart his course in life. He never forgot that as he began to build his own coaching career, starting as a JV coach at Ahrens High School.

Davenport spent 10 seasons at Ballard High School and coached two of the more celebrated high school players in Louisville history – DeJuan Wheat and Allan Houston. He won the Kentucky state championship in 1988.

He then became the only assistant coach to span the University of Louisville careers of Hall of Famers Crum and Pitino.

Davenport also spent one season as an assistant coach to Mike Polio at Virginia Commonwealth, on a staff with future Kentucky coach Tubby Smith.

Everybody knows Davenport. Mike Krzyzewski sang his praises.

"That team, those kids and coaches are champions," Krzyzewski said after Duke played Bellarmine in 2012. ". . . For our guys to play against their team, veteran team, so well coached, was excellent for our basketball team."

After Bellarmine made the move to Division I, Krzyzewski twice brought Davenport and the Knights back to Cameron Indoor Stadium – including for the program's first-ever Division I game, and made sure the school was paid a full visitors share even when the crowd was diminished by social distancing after COVID. He helped Bellarmine set up a second road game -- at Howard University -- after its game at Duke in 2021, which was the program's first win as a Division I program.

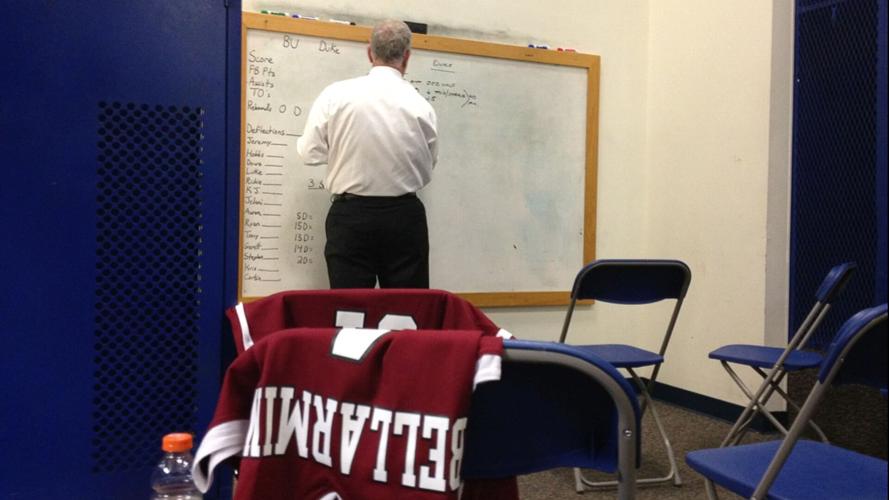

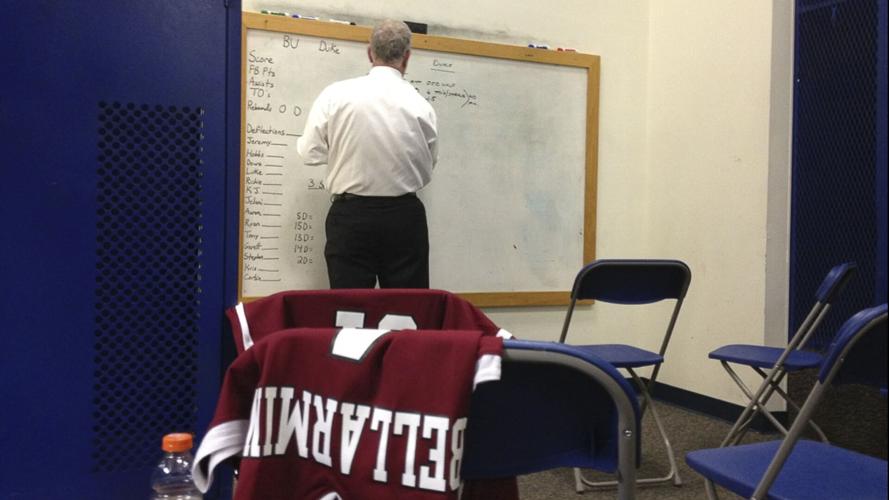

Bellarmine coach Scott Davenport writes the game plan on a white board in the locker room before a game against Duke in Cameron Indoor Stadium in 2012.

Other coaches paid tribute differently. While at Arkansas, Eric Musselman said after seeing Bellarmine on tape, "I wouldn't want to play them. I've never seen a team pass the ball so much in my life. I've never seen a team not dribble the ball like that."

When Davenport's Bellarmine teams were at their best, they could pack into a 40-minute college game nearly as many passes as an upper-level NBA team fits into a 48-minute game.

Making a Difference

But always, Davenport has been about more than the basketball. You could find him in Knights Hall with a dust mop sweeping the basketball court, or on a ladder wiping the smudges off the backboards. If you ran into him in the grocery store, chances are he was stocking up on snacks for the next road trip.

Every night at bedtime on road trips, coaches would throw little goody pouches onto the hotel beds of players, wrapped in a motivational message for the next day's game.

It was not a life of charter flights and five-star hotels. It was cold bus rides in the Midwest in the dead of winter, Davenport sometimes getting off of the bus to walk part way down the exit to see if it was clear enough to keep going.

He fought for everyone in his programs, from the most decorated players to the student managers. He worked tirelessly to raise money for Bellarmine's managers and took great pains to make sure his players respected and understood the work they did.

Kids from underprivileged backgrounds or in difficult life circumstances had no better friend than Davenport. Seth Walsh, a young cancer survivor, was adopted by the team at age 7 after a series of grueling medical encounters. At Davenport's last home game, he was there with his family, celebrating three years cancer free. Davenport went through a pile of NCAA red tape to let leukemia patient Patrick McSweeney get onto the court to score a basket for the Knights and made McSweeney an honorary team member.

Bellarmine coach Scott Davenport gets a hug from Juston Betz during Senior Day ceremonies in 2023.

There are others, more stories than I know, more than he would want me to write. At Bellarmine's opening exhibition this season, the program played host to students from around the city for an 11 a.m. tipoff. One of the schools represented was Frayser Elementary, where Davenport went to school. He remembered appearing at the school when it won an award for raising its test scores, and watching a fifth-grade student speak to the class while a classmate translated into Spanish.

As he watched, Jefferson County Public Schools' superintendent Marty Polio leaned over to him and said, "It wasn't like that when you were here, was it?"

Davenport knew the principal was bringing some buses from Frayser to his exhibition game, and before they departed from Knights Hall to go back to the school, he gave her a piece of paper with a name on it, and told her to stop at the McDonald's on the way, where he had bought 80 Happy Meals for the kids as they headed back to class.

"Wouldn't it be great if some of those kids came to this campus and thought, I can go there. I can do what they are doing," Davenport said.

And sometimes if he found one of those young people, he would do more than that. He brought Michael Parrish to Bellarmine from Fern Creek High School knowing that the recruiting services would say he didn't belong. But he wanted to give Parrish a chance. He knew Parrish had experienced some hardship, remembered hearing about times when maybe the family would drag a hose over from the neighbors' house when the water was cut off.

Parrish, over his time at Bellarmine, became a contributor, went on scholarship, and played in a Final Four. Today he works for Apple.

The final scorecard for Davenport shows a Hall of Fame record of the only coach ever to win championships in the KHSAA and NCAA.

But the numbers barely tell the story. He has been a basketball constant in this city for four decades. And, I suspect, he will continue to be, in one role or another. If we're lucky.

He'll also turn his attention to family.

"I am very proud of earning an education and teaching/coaching in every corner of our community," Davenport said. "I appreciate my wife, sons, daughters-in-law, two wonderful grandchildren, sister and grand dog sharing me most of their lives with the game we love so much."

After he joined the JV team at U of L, and knew he wanted to be a coach, Davenport read everything he could get his hands on by or about John Wooden. He studied Crum, who had played for and coached with Wooden.

Somewhere, no doubt, he ran across the piece of a poem Wooden liked to recite to demonstrate the qualities of a great teacher. He must have, because he grew to embody them over a decorated coaching career.

No written word, no spoken plea

Can teach the youth what they should be;

Nor all the books on all the shelves –

It's what the teachers are themselves.

Davenport's son Doug, who has been his associate head coach since 2016 and was named Bellarmine's coach-in-waiting in 2022, is expected to officially be named to the head coaching position soon.

"If granted one wish," Scott Davenport said at the end of his retirement statement, "I wish I could do it all over again!"

Copyright 2025 WDRB Media. All Rights Reserved.