In recent years, most people have heard the phrase “the polar vortex”, which has made regular appearances in media headlines, often with an exciting, albeit sometimes ominous “Day after Tomorrow”, flavor:

- “Get ready: here comes the polar vortex”

- "Northeast U.S. latest to experience polar vortex temperatures”

- “Polar vortex invades central U.S.”

- “Polar vortex breaks record-low temps, snaps steel, empties cities”

But the “polar vortex” is not actually a synonym for “cold snap”; rather, it’s a well-known feature of Earth’s atmosphere that describes the high-altitude winds that blow around the pole every winter, miles above us in a region called the stratosphere.

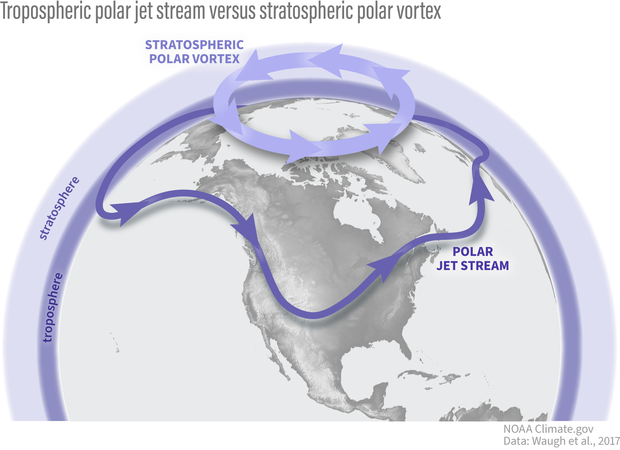

The polar vortex is in the polar stratosphere, above the layer of the atmosphere (the troposphere) where most weather, including the jet stream, occurs. NOAA Climate.gov graphic.

The stratospheric polar vortex forms in the winter hemisphere when the Earth’s pole is pointed away from the sun. The polar stratosphere enters darkness and becomes cold relative to the tropical stratosphere. The temperature contrast makes for strong winds in the stratosphere that blow from west to east. This wintertime stratospheric wind is what we call the Arctic polar vortex.

An atmosphere dance party: who’s the wallflower, and who’s the extrovert?

If we were at a dance party, your first impression might be that the stratospheric polar vortex is the wallflower standing alone on the upstairs balcony, while the tropospheric jet stream is showing off on the dance floor with its flamboyant troughs, ridges, and cut-off lows. But as is so often true, first impressions are not always correct: while the polar vortex often doesn’t mind doing its own thing, it is not a passive watcher of the atmospheric dance down below. With some encouragement, polar vortex can actually become one of the most dynamic dancers there.

Making an impression

Why does the polar vortex matter to us, given it is so high and far away in the polar atmosphere? One of the main reasons is because the vortex does not always sit quietly by itself. Though it might (literally) need a little push from the troposphere to get its groove on, it can really break down with a move called a “sudden stratospheric warming”.

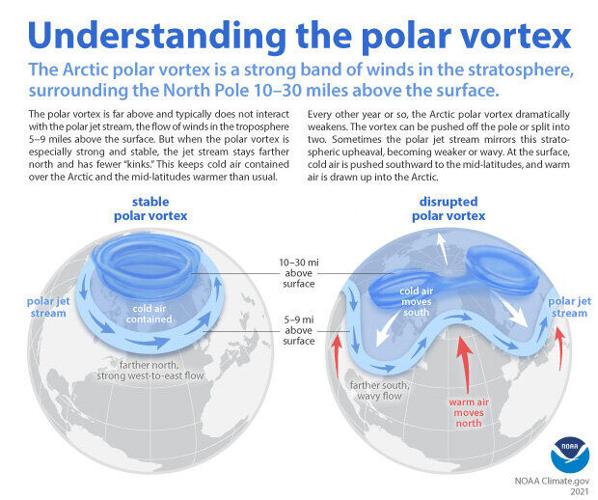

In this move, the polar vortex may wobble, swing far from its normal position over the pole, or stretch itself way out, sometimes even splitting in two (doing the “splits”? We can hear the groans from here…). And when this happens, the chances of cold weather across many populated regions can increase for many weeks afterwards.

When the Arctic polar vortex is especially strong and stable (left globe), it encourages the polar jet stream, down in the troposphere, to shift northward. The coldest polar air stays in the Arctic. When the vortex weakens, shifts, or splits (right globe), the polar jet stream often becomes extremely wavy, allowing warm air to flood into the Arctic and polar air to sink down into the mid-latitudes. NOAA Climate.gov graphic, adapted from original by NOAA.gov.

Alternatively, sometimes the vortex does another extreme move where it becomes super fast and stable, encouraging the cold air at the surface to stay over the pole, which increases the chances of winter heat extremes in some regions. We will be getting into all the details of these events and their influence on our weather in future blog posts.

Polar vortex groupies

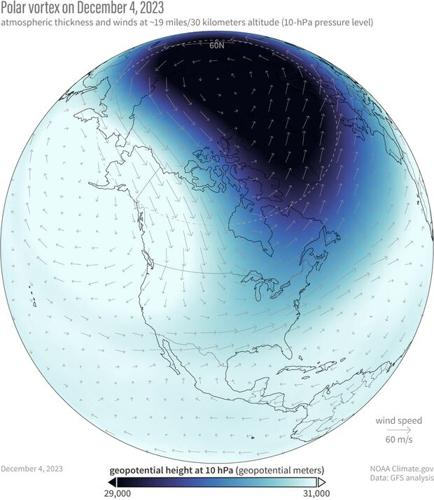

It’s hard to not be fascinated by the strong silent type that suddenly wows you with its awesome dance moves, particularly when those moves can cause extreme weather impacts, so scientists and forecasters have increasingly appreciated the need to monitor what the polar vortex is doing. We usually start by looking at the zonal (east-west) winds at 60N (the latitudes near Anchorage, AK or Oslo, Norway) at around 19 miles (30 kilometers) in altitude, where the air is so thin that the pressure is only 10 millibars (10 hectoPascals). By looking at a time series of these zonal winds we can get an idea of whether the polar vortex is really strong and stable, or weakening and ready to bust into its sudden stratospheric warming moves.

The polar vortex on December 4, 2023. Because the air within the polar vortex is generally much colder than the air outside of it, the polar vortex shows up on maps of atmospheric thickness ("geopotential height") as a region of low thickness. The 10-hectoPascal geopotential height is the altitude at which the pressure is 10 hectoPascals. NOAA Climate.gov image, based on Global Forecasting System (GFS) data from Laura Ciasto.

So what’s the polar vortex doing now? For the last few weeks it’s been embracing its wallflower persona as it sits over the polar region with stronger than average westerly winds. However, it does look like the stratosphere is at least thinking about joining the winter dance. If we look at the average of all the model forecasts from NOAA’s operational forecasting system (known as the Global Ensemble Forecasting System, or GEFS), it predicts that the zonal winds will weaken through the start of the new year.

The real question is whether the polar vortex just wants to dance in place (like it often does) or really show its steps. If we look at the individual forecasts that make up the average, some indicate that those polar vortex westerlies will not only weaken but change direction to blow from east to west, which is how we define a sudden stratospheric warming. In addition, the leading forecast system for Europe (the ECMWF model, short for European Centre for Medium-range Weather Forecasting) shows an even higher likelihood that the vortex will be weaker than normal during December. These hints of a shift towards a weaker polar vortex means we will keep a close eye on whether the polar vortex wants to join an early winter party or sit this one out.