"Our dead are never dead to us until we have forgotten them …" - George Eliot

LOUISVILLE, Ky. (WDRB) -- The dead at Eastern Cemetery aren't forgotten, but many are neglected.

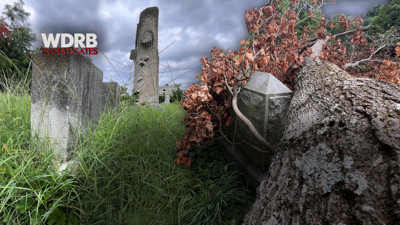

Headstones sink into the rolling hills. Bags of dog feces hang above a fading 19th century marker. A downed tree limb covers at least five graves. Grass grows tall around much of the graveyard.

Eastern has been abandoned for decades now, one of three cemeteries once owned by the Louisville Crematory and Cemeteries Co. before its owners were indicted on criminal charges and the company dissolved into bankruptcy by the early 1990s.

Without an owner, it's up to volunteers to maintain the grounds and cover the cost of the work. For 23 years, a succession of Jefferson County judges has overseen myriad requests, from approving family members' petitions for new monuments to signing off on grass cutting schedules and reviewing how money from a trust fund is spent.

Harold Dawson has helped to maintain the Baxter Avenue cemetery that abuts its more well-known and opulent neighbor, Cave Hill Cemetery. He and his wife, Peggy, were working on a recent afternoon taking care of family graves.

"What makes you sick is when you see all the others with huge limbs around them and 6-foot-tall grass and stuff," Dawson said. "... every grave should have the same care."

Harold Dawson, who has family buried in Eastern Cemetery, talks with WDRB News, August 16, 2024 (WDRB photo).

But, in recent years, the system with responsibility over Eastern, Schardein and Greenwood cemeteries has failed the families whose loved ones are buried there, a WDRB News investigation has found.

The court-appointed supervisor who oversaw cemetery expenses ended his work in 2018, court documents show. In 2019, then-Attorney General Andy Beshear's office told a judge it was "diligently working" to find a successor. That didn't happen under Beshear, a Democrat who is now Kentucky's governor, or under the next attorney general, Republican Daniel Cameron.

The office of the current attorney general, Republican Russell Coleman, declined to answer specific questions about the process, issuing a statement from spokesman Kevin Grout that said: "The Attorney General's Office continues to work with our partners to find a responsible long-term solution that will provide a level of dignity for those laid to rest and their families."

Meanwhile, as volunteers pay for cemetery upkeep themselves, no one knew there was money in a cemetery account until recently. In all, according to court filings, $43,071.40 remains in that account and hasn't been spent.

"What seems to get lost in all the bureaucracy and politics is that this should only be about respecting our dead and the relatives that still come to grieve for them," said Andy Harpole, president of the nonprofit group Friends of Eastern Cemetery.

Like others, Harpole said he wasn't aware of the unspent money in the operating account until recently. He called it a "meaningful amount" that could be making a difference, especially if there had been the court-appointed representative in place to spend it.

"To me, the lack of respect for our dead, sadly, says a lot about the mindset of those who are supposed to be representing our community," he said.

No answers about cemetery money

The cemeteries take in about 52 acres in different Louisville neighborhoods: Schardein, the smallest at about 3 acres in Taylor Berry near Churchill Downs; Eastern, the largest at 28 acres in Cherokee Triangle, and Greenwood at 21 acres in Chickasaw.

They were owned and managed by the Louisville Crematory and Cemeteries Co., which was administratively dissolved in 1992, state records show. Several years before, its top executives were charged criminally for corpse abuse, grave desecration and failing to keep adequate funds in perpetual-care and maintenance trust accounts, according to Associated Press coverage at the time.

Investigators reportedly found as many as 48,000 bodies buried in graves in Eastern and Greenwood cemeteries that already were occupied. Those abuses are top of mind to volunteers like Dawson, who tends to his family's gravesites at Eastern.

Bags of feces hang above a 19th century grave marker in Eastern Cemetery, one of three cemeteries abandoned by its former owner, Louisville Crematory and Cemeteries Co., August 16, 2024 (WDRB photo).

"Especially on the older ones, there's no telling how many other occupants are on top," he said. "I'd really hate to turn over the dirt and see."

After the cemetery company dissolved, more trouble followed. In 2001, Democratic Attorney General Ben Chandler took legal action against a court-appointed receiver accused of misusing funds. After that, the stewardship fell to Jefferson Circuit Court, where it remains.

Also in 2001, the court appointed Charles Rickert as the "fiscal intermediary" to use funds from a trust held by PNC Bank for the cemeteries' care. Working under a contract with the Kentucky Attorney General's Office, Rickert used a bank account to spend earnings from the trust fund on things such as fence repairs and payments to Dismas Charities for maintenance work, court documents show.

Rickert filed regular reports with the court until early 2018, the last one included in records reviewed by WDRB. Dated Feb. 16, it shows a balance of $4,171.56.

Rickert was not replaced after his contract ended in 2018. He died in 2023.

In late July 2024, a Louisville-based attorney for PNC told Jefferson Circuit Judge Patricia "Tish" Morris that he believed there was $43,071.40 in Rickert's account — that only he had authority to spend — and asked for her to move the money to the trust fund.

PNC suspects the money wasn't spent because of Rickert's contract ending and his subsequent death, court documents show. Morris ordered the funds to be transferred in a ruling Aug. 14.

A fallen tree limb at Eastern Cemetery, August 16, 2024. (WDRB photo)

The Louisville attorney, Jeremy Gerch, did not respond to a request for comment. PNC spokeswoman Karyn Ostrom declined to answer these specific questions: How and when did PNC discover the funds in this account? Why weren't they discovered sooner? What steps has PNC taken, or plan to take, to ensure that the money is spent properly and expeditiously? What action, if any, did PNC take to advocate for a replacement for Rickert?

Ostrom said in an email that "the duty of confidentiality that accompanies being a trustee hinders us from providing the specificity you are looking to gain through your line of questioning."

She said PNC "is committed, as always, to fulfilling its duties as trustee and will continue to work through the courts and with the Office of Attorney General to help satisfy the purposes of the trust to provide for the care of the cemeteries formerly operated by the Louisville Crematory and Cemeteries Company. This is reflected in the court record."

Ostrom further said that PNC can only act as directed by the court with the approval of the Attorney General's Office.

As a general rule, judges must operate on the assumption that their orders are being followed, said McKay Chauvin, a retired judge who now is chief court administrator in Jefferson County.

In a statement, Chauvin said those judges "are only prompted to act or react when an interested party files a written motion letting them know that something is 'wrong' and asking them to make it 'right.'"

'God' and a few people

With no disbursements from the cemetery care fund since 2018, volunteers, nonprofit groups and others maintain the properties and continue to cover the costs themselves.

Staff at adjoining Cave Hill Cemetery cuts grass at Eastern Cemetery at its own expense, said sexton Brian Myers, who was supervising a work crew on a recent afternoon. Cave Hill helps out to be involved in the community and neighborhood, but the work does take away from other responsibilities, he said.

"It's on our hours," he said. "We're paying our employees to do work somewhere that is not making any kind of income for us at all."

Lloyd Davis (left) and Shedrick Jones Sr. (right) visit Greenwood Cemetery in Louisville's Chickasaw neighborhood, August 16, 2024. They have volunteered to maintain the abandoned property for years. (WDRB photo)

At Greenwood Cemetery in western Louisville, groups like the National Association for Black Veterans and the Greenwood Cemetery Community Partners fill the void, mapping hundreds of veterans buried there and doing basic maintenance like grass trimming and removing downed limbs.

"I talk about God, and a few people, and God and a few people have kept it down to where it is now," said Lloyd Davis of the veterans association. "And I thank him for sending a few people and I know that he will continue to send a few more."

Greenwood is home to the gravesites of prominent Black Louisvillians such as Alberta Jones, the first woman named city attorney in Jefferson County and whose 1965 murder has never been solved; Henry Fitzbutler, Louisville's first Black physician, and Elijah P. Marrs, who helped establish what became Simmons College of Kentucky.

Volunteers, including from Louisville's parochial schools have helped with cemetery upkeep, but there are "breaks in service," such as when school is out, said Shedrick Jones Sr., Kentucky state NABVETS commander.

"We have some connections, but there is no legal force in place that makes government want to pull this cemetery in and put it under their umbrella," Jones said. "And that is actually what needs to happen."

"The city takes care of other cemeteries," Davis said. "They take care of other cemeteries that have been closed. The parks department just takes it over. They cut it, but they won't do this."

'I don't think that's sustainable'

They, like other advocates, want a new approach to the court-led management of the cemeteries for the last two decades.

Kentucky state Rep. Pamela Stevenson, D-Louisville, has sponsored legislation in the General Assembly in recent years that would force Metro government and other cities to require cemetery owners to "properly care for them." The bill hasn't advanced.

While the legislation would not affect Eastern, Greenwood and Schardein cemeteries, Stevenson said she views it as a "first step" for subsequent action to address these sites.

"We have to look to see what the roadblocks are in order to fashion an appropriate solution," she said.

Stevenson, who represents parts of the city's west end, acknowledges she doesn't know what that solution looks like now.

"Once we come to a meeting where we can theorize, strategize about what to do, that's one level up from where we are now, which is people doing it piecemeal the best they can," she said.

Kentucky state Rep. Pamela Stevenson speaks at Greenwood Cemetery, August 16, 2014. She has sponsored past cemetery legislation in the Kentucky General Assembly. (WDRB photo)

Metro Council member Tammy Hawkins, D-1, pushed last fall for greater Metro government involvement in Greenwood Cemetery's upkeep. She told WDRB this month that city officials "really haven't even followed up."

Eastern, Greenwood and Schardein cemeteries are Louisville Mayor Craig Greenberg's top three "cemeteries of concern," according to April minutes of the Louisville Cemetery Board, which the mayor appoints.

Those meeting minutes say the board has determined that the three cemeteries fall under its jurisdiction.

Kevin Trager, spokesman for Greenberg, a Democrat, said the board is now meeting regularly to discuss ways to support more than 100 private abandoned cemeteries across Louisville, including Eastern, Greenwood and Schardein. Their focus, he said in a statement, is finding volunteers for regular maintenance, among other things.

Louisville Parks and Recreation manages five publicly owned cemeteries.

"Metro Government has no intentions of taking ownership of additional cemeteries," Trager said.

Mike King, whose Greenwood Cemetery Community Partners was organized in 2023, said there needs to be "more administrative control" over the properties, since volunteer groups come and go.

"I don't think that's sustainable for the long, long term," he said.

Ideally, King said, Metro government would establish a standalone, government-supported foundation that would have control over the cemeteries and the resources to maintain them.

"No one really seems to know how to get this thing totally organized and where to go for it," he said. "We talk about it. But there needs to be more to it than that.

"I think they need to sort of sit down and brainstorm and go from scratch, and throw out the old and bring in some new perspectives."

A grave sits next to a downed tree limb at Eastern Cemetery. Aug. 16, 2024. (WDRB Photo)

Copyright 2024 WDRB Media. All Rights Reserved.