LOUISVILLE, Ky. (WDRB) -- In a fast-growing part of eastern Jefferson County, organizers are working to form a new suburban city in the mold of Jeffersontown, Middletown and others that operate independently but also alongside the merged city-county government.

Creating "home rule" cities hadn't been allowed since voters chose to combine the county and the old city of Louisville in 2000, but that ban ended after state legislators passed new laws for Louisville Metro government in recent years. Among them: letting residents in parts of the county petition for new cities.

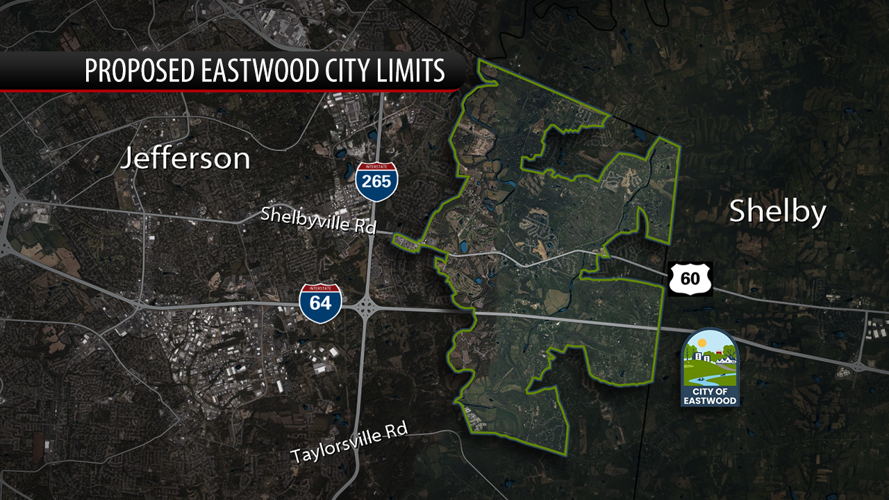

The proposed city of Eastwood would cover a swath of subdivisions, undeveloped land, parks and other areas mostly east of the Gene Snyder Freeway and Shelbyville Road. A WDRB News analysis of available maps shows a proposed boundary taking in more than 19 square miles — roughly twice as big as Jeffersontown, the county's largest suburban city.

The proposed city of Eastwood would cover a swath of eastern Jefferson County

The effort is the first since the Kentucky General Assembly lifted the moratorium in 2022, allowing residents to form cities of more than 6,000 people starting this year. And it could be a harbinger of things to come in other unincorporated areas.

With new property taxes and government authority at stake, the Eastwood debate has spilled over into Facebook groups and on yard signs in this formerly rural area now teeming with housing, commercial and other development. Backers aim to get enough signatures by next spring to formally make Eastwood the first new Jefferson County city since merger.

Supporters say they simply want the hyperlocal powers and services that come with an independent city, from extra police coverage to dedicated road money. But they have elevated one issue above all: having ultimate control over zoning matters.

Rezoning and other key land-use decisions in Jefferson County largely follow a process that includes a review by the Louisville Metro Planning Commission, which then sends recommendations to the Metro Council for a decision. But that's not the case in 12 small cities, from Shively to Anchorage, that have their own final say.

A new city of Eastwood aims to join that group.

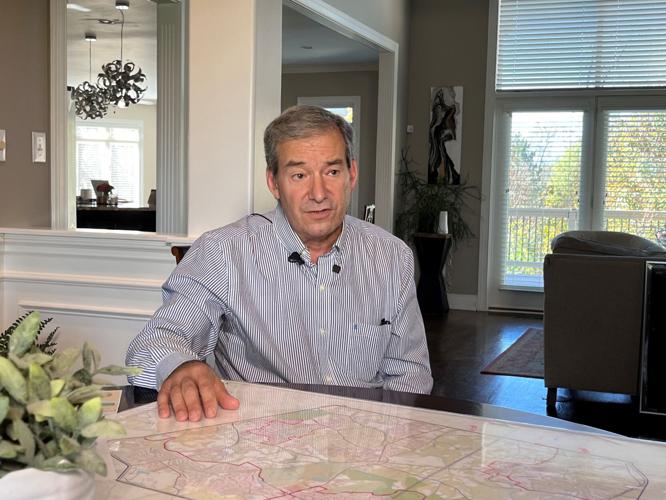

"Zoning authority is an extremely powerful tool to allow a community to have input into the process of what goes on there," said Bob Federico, chairman of the Eastwood Incorporation Committee. "Currently, this entire area — the entire basically east end east of the Snyder (Freeway) — has no legislative ability to do anything."

"We're not asking for more," he said. "We just want to have the same rights and ability to make decisions within our area."

Bob Federico, chair of the Eastwood Incorporation Committee, talks about the plan to create a new city of Eastwood, November 12, 2024 (WDRB photo)

The Eastwood push comes as Louisville Mayor Craig Greenberg's administration works to make changes to the Land Development Code, the wide-ranging set of rules for land use in Jefferson County. Those recommendations include allowing "missing middle housing" — projects like small duplexes, triplexes and fourplexes — on property now zoned for single-family homes in a bid to ease Louisville's affordable housing shortage.

But creating a new city with zoning power alarms some opponents, including affordable housing advocates and real estate developers.

Tony Curtis, executive director of the nonprofit Metropolitan Housing Coalition, argues that the sheer size of the Eastwood plan is worrisome because a new city could decide not to implement Metro land code changes. Such a move, he said, could make it harder to build affordable and other housing in a large area.

"Ultimately, that is problematic for affordable housing development, for housing development, because it gives a new city zoning authority," Curtis said. "They don't have to adopt any land development code reforms that may occur."

'Middle housing' debate

Housing advocates long have decried a shortage of affordable housing in Louisville. A city report released this year found that there is a surplus of homes for median-income households, but more than 36,000 units are needed for the lowest-income households.

One approach pushed by Greenberg in his My Louisville Home housing strategy is what's known as "middle housing" — the type of multifamily buildings commonplace in Louisville's older neighborhoods. The city's Office of Planning is proposing a "re-legalizing" of the housing in areas now zoned for residential housing.

The Planning Commission is holding a public hearing on some of those changes Thursday.

Eastwood city planners are galvanizing around the land code discussion. They note that the other cities in Jefferson County with their own zoning authority aren't required to adopt the Metro government changes — something Eastwood could do if it incorporates next year.

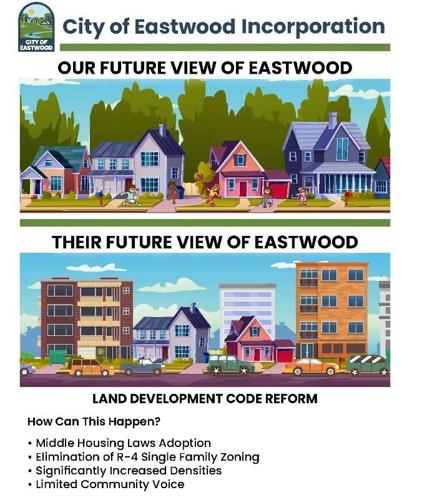

The Eastwood website includes a graphic with two residential streets. One labeled "OUR FUTURE VIEW OF EASTWOOD" shows four single family houses with children playing outside. Another labeled "THEIR FUTURE VIEW OF EASTWOOD" depicts taller buildings crowding next to houses.

The website warns that the changes to the land code would bring traffic, possible changes in property values and a "dramatic change in area aesthetics and character."

Curtis takes issue with such language.

"Changing the character of the neighborhood is a problematic phrase that's been used throughout history to exclude groups of people from certain geographic areas," he said. "This is an opportunity to say, 'Hey, we're not going to draw a red line around a big swath of eastern Jefferson County because we want to keep people out. We need to look for solutions.'"

Tony Curtis, executive director of the Metropolitan Housing Coalition, November 12, 2024 (WDRB photo)

But Federico, who is spearheading the incorporation effort, bristles at any talk of excluding people. He said Eastwood supporters want to make sure that sidewalks, public transportation and other infrastructure are in place before middle housing is built.

"I don't think that we're saying we don't want middle housing in this area," he said. "We just want to make sure that you put it in a place within the area that that makes sense for the people who live there."

Meanwhile, a movement opposing the incorporation called East End Neighbors is behind a website and yard sign campaign that urges residents to resist the "East End Tax."

A WDRB reporter requested an interview Nov. 5 through the group's website, which doesn't provide details about the organization's membership or its leadership. There was no response.

East End Neighbors does not reveal information about who created its website. The group is listed as a nonprofit organization on its Facebook page; there is no listing for "East End Neighbors" on the Kentucky Secretary of State's business entity website or the IRS' online portal of tax-exempt organizations.

A yard sign on Flat Rock Road opposing the incorporation of Eastwood in eastern Jefferson County, December 3, 2024 (WDRB photo)

Juva Barber, executive vice president of the Building Industry Association of Greater Louisville, told WDRB this week that some of its members are part of the organization, along with certain property owners. She did not name them.

Barber said that while the initial reasons put forth for the new city included additional services, such as police coverage and trash collection, "more and more of the comments were anti-development, anti-growth."

"I have several members who own property out there and they were very concerned with what would this do to their ability to provide the service that we provide, which is additional housing and development," she said.

New taxes and new services

An Eastwood city would operate similar to other independent cities. Plans call for a police force, public works department, city attorney and administrative staff. A mayor and four city council members would be elected by voters.

A preliminary budget envisions $5.9 million in revenue in 2026, with residential property taxes of $3.2 million accounting for more than half of that. Like other small cities, residents of Eastwood would pay city property taxes in addition to their Jefferson County property taxes.

The new city also would rely on the insurance premium tax that life, auto and other insurance policy holders now pay to Louisville Metro government. Those funds instead would go to Eastwood, generating an estimated $2.1 million a year.

A sign on Flat Rock Road supports the plan to create a new city of Eastwood in eastern Jefferson County, December 3, 2024 (WDRB photo)

It's the new property taxes that are at the crux of one part of the debate: Would the extra tax be worth it?

In some cases, the answer depends on whether people live in a subdivision with a homeowners' association that contracts for security and trash collection or in more rural areas facing development pressure.

The Polo Fields subdivision no longer is part of the Eastwood boundary, but resident Javid Beykzadeh has followed the discussion for months. He noted that the Polo Fields already handles garbage pickup, for example.

From his perspective, Beykzadeh argues there's "potentially not a lot of benefits attached to that increase in taxes."

"A lot of people just don't want to pay the additional taxes because they don't seem like it's going to be a benefit even though there's the police, some local control over zoning — people don't feel Like it's going to be sustainable," he said.

Others do see a benefit. Robert Reed, who lives in the Gardiner Park subdivision, said the forecasted property tax increase of $500 annually for a $350,000 house is worth it.

"This would be offset by services that would be provided by the city," he said, including trash pickup and additional police.

Taxes aside, Reed said he would welcome the zoning power of the new city. "One of the major advantages is we would have input into new developments going in on our already overcrowded and very busy streets," he said. "They're very unsafe in a lot of areas."

David Henderman, who signed the Eastwood petition with his wife, Beth, said having a larger say into planning decisions in the area is the main reason the couple supports the new city. He said traffic on "inferior roads" is a growing concern, including school buses traveling to and from the new Echo Trail Middle School.

"It's a very difficult situation, and traffic on those roads is getting to be more and more all the time," he said.

Louisville Metro Council member Anthony Piagentini participates in a meeting on Dec. 5, 2023. By Chris Otts, WDRB News

Residents still would have Metro Council representation. Three Republicans — Anthony Piagentini, Stuart Benson and Kevin Kramer — now serve the area being considered for Eastwood.

Benson said he's leaning toward favoring the new city plan, although he told WDRB he has concerns about the size of the proposed city and creating more government in general.

Piagentini said he's not taking a position on the incorporation drive, adding that he just wants people to be well informed.

The changing boundaries that now exclude the Polo Fields means that less of Piagentini's district would be in Eastwood. Still, he has followed the debate and said it appears clear that annexing unincorporated parts of the county into existing cities is easier than forming a new city.

Much of the proposed Eastwood area leans right politically and live in subdivisions with homeowners' associations that function as efficiently as government, he said. "Some of those folks are generally skeptical of government. So to add a layer of that may or may not be something they're interested in."

"I think they've got the low hanging fruit," Piagentini said, referring to the Eastwood organizers. "They've got the people that were very engaged and wanted to see the change. But bringing on the rest of the people that are needed is not easy."

Kentucky lawmakers lift new city ban

The Eastwood push is the result of changes to state law governing the city-county merger.

The consolidation that took effect in 2003 allowed more than 80 small cities in Jefferson County to remain intact but it prohibited the creation of new ones. Instead, residents in unincorporated areas could form "service districts" to get additional services — although that hasn't happened.

With the dome under construction, the Kentucky State Capitol in Frankfort. (WDRB image by Adi Schanie) June 6, 2024

State lawmakers began to chip away at new city ban in 2021 when a Republican-backed bill in the Kentucky General Assembly proposed letting residents form new cities.

The measure didn't pass, but a group of Louisville-area GOP lawmakers introduced a similar bill in 2022, arguing that citizens should be allowed to create new small cities, especially outside the dividing line of Louisville's Urban Services District.

That district — the boundary of the old city of Louisville — levies higher taxes but gives residents access to services like trash collection that aren't available outside it.

Critics labeled the bill a "war on Louisville" that sought to unravel gains of merger and put Metro government revenue and population-linked funding in jeopardy. The measure passed and became law after legislators voted to override a veto from Democratic Gov. Andy Beshear, who said in his veto message that the bill "imposes changes on Louisville's government, without the consent of the people of Louisville."

The new law let voters in unincorporated areas in Jefferson County outside the Urban Services District form new cities of at least 6,000 people if 66% of the voters in the proposed city limits sign a petition.

Lawmakers amended that process this year, making the threshold at least 60% of "registered and qualified voters" equal to all votes cast in the last presidential election.

Douglass Hills Mayor Bonnie Jung, vice president of the Jefferson County League of Cities, long has been an advocate of new cities in the county. She said in an interview that it's become clear that the Eastwood push centers around zoning power.

Douglass Hills is one of the 12 cities with that authority. Jung said the city has used it in recent years to ensure that a commercial building was designed to similar standards as others in a shopping center — a small issue, she conceded, but one that shows the importance of local control.

"Now you've got places like Eastwood that they have no control over anything," she said.

Eastwood organizers had about 30% of the needed signatures in early November and are working to add to that count, Federico said.

"It has been a little more challenging than we anticipated," he said. "It's very easy to get people to sign a petition to do something good. It's harder to get them to sign that petition when there are a couple dollars that have to come out of their pocket. And I get it. I totally get it.

"But you have to ask yourself: What are you getting for what you pay today? What we're talking about is not one-tenth of that. Maybe it's one-15th of that. And you're getting real, tangible benefits."

The push for a new city in eastern Jefferson County comes amid a debate on housing reforms backed by Mayor Craig Greenberg.

Copyright 2024 WDRB Media. All Rights Reserved.