LOUISVILLE, Ky. (WDRB) -- On any Sunday, listen to Louisville between 9 a.m. and noon. You can often hear majestic sounds of a community rejoicing, shouts of praise and worship filling the atmosphere from churches on almost every corner. And when you feel that kind of spirit, it's hard to imagine Sunday is also Louisville's most dangerous day.

Louisville Metro Police Department statistics show gunfire and murder at their worst on Sundays in 2021, with more than 40 homicides and nearly 100 non-fatal shootings as of the end of October.

Hours before the church doors open, as ministers sleep, mothers weep, sometimes at crimes near the steeple on the exact same street. Sunday, the day of rejoicing, starts with a chorus of heartbreak in Louisville. And instead of the shouts of praise and worship, it's agony and disbelief.

“I just tell anybody who's going through what I'm going through to just hold on and pray,” Sherita Smith said. “That’s what I’m doing to get by every day.

Smith hadn’t been to church for quite some time. She avoided crowds in the COVID-19 pandemic. Little did she know that it wouldn’t be the pandemic — but the epidemic — that shattered her home and brought her back to the sanctuary to say goodbye.

"I don’t want to cry no more," Smith said from the podium at the funeral for her son, Tyree Smith. "I want justice. I don’t want to cry no more."

The 16-year old Eastern High School junior was shot and killed in a drive-by as he waited with a group of students for his school bus around 6:15 a.m. on Sept. 22. Two other students hit by the hail of bullets survived. As Smith laid bleeding in the street near the intersection of Dr. W. J. Hodge and Chestnut streets, he called his mother’s cell phone shouting, "Mama, I’m shot! I’m dying."

They’re the last words Smith said she heard from her son.

Tyree Smith

"The only thing I ever thought I had to worry about was COVID," she said. "I never thought it would be crime. It makes the blow more hard. What's going on in Louisville is ridiculous. They're not giving this younger generation a chance to grow."

Tyree Smith's senseless death is just one of the many examples of what’s going on in Louisville. The city has seen more homicides and shootings in 2021 than any year in its history. City leaders describe the surge of gun violence plaguing the city as an epidemic.

"Every day, it's murders, murders, murders," Eric Shirley, Tyree Smith’s stepfather, said while sitting in the family’s Russell neighborhood home. "It’s crazy. You are hurting whole families and you are destroying generations.”

Bullets flew near Smith’s bus stop in the early morning hours in the weeks before he was killed. Students alerted their school, but the location of the stop wasn't moved until after the drive-by.

Smith's parents do not believe their son — who worked at McDonald's, cut hair and loved editing videos — was the target. And neither does the city’s police department.

"(LMPD) said he didn't have no beef with anyone," Smith said. "No threatening messages in his phone, nothing on social media, no arguments, fighting, gang activity. Nothing."

At Smith's funeral, Louisville Mayor Greg Fischer gave the family a proclamation mourning a life lost to a senseless and selfish act.

"They have taken a hard-working, good young man that genuinely cared about people,” Smith said. "I just want justice for my son."

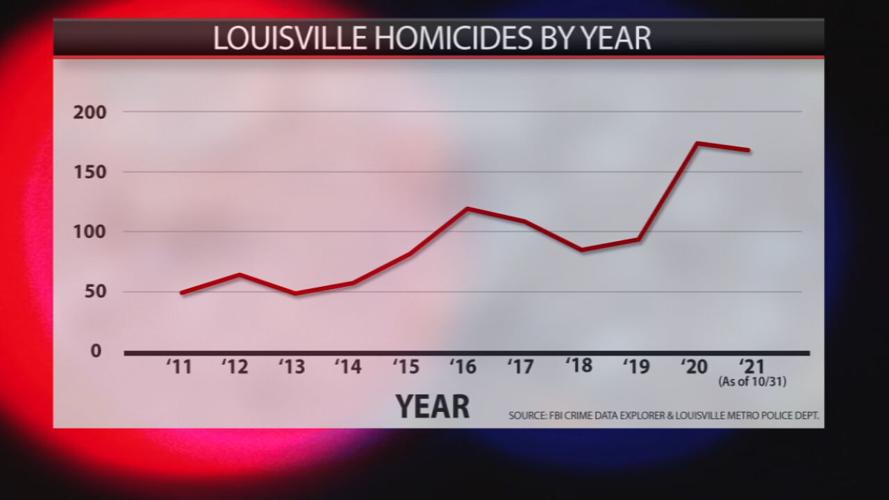

FBI data shows Louisville homicides steadily climbing in the last 10 years. The city hovered around 50 murders a year in 2011 and is now on track to reach about 200 by the end of 2021, which would mark a 300% increase in the last decade.

Data from every homicide in 2021 through the end of October shows 40% of the 167 homicide victims are age 25 or younger. The data reveals a crisis among young people: Twenty-one homicide victims are under 18, and five people killed were under the age of 10. There were also 83 juveniles victims of non-fatal shootings. Overall, roughly 75% of the homicide and shooting victims in Metro Louisville are Black, and the majority of the cases happen in west and central Louisville.

The city hovered around 50 murders a year in 2011 and is now on track to reach about 200 by the end of 2021, which would mark a 300% increase in the last decade.

Out of the few arrests made, six were juvenile shooters, according to police, with the youngest being a pair of 14-year-olds.

"Somebody threw a bomb firework, and it was very smoky, and the person was in their car, and they were shooting, and I guess they couldn't see where they were aiming and shot my sister," 7-year-old Kennedy Clancy said as she colored a picture on a playground. "When I hear sirens, it just makes me think about her."

Kennedy witnessed the murder of her sister, Nylah Linear, on July 22. Nylah, Kennedy and their other sister — 15-year old Sakinah Abdul Jalil — had gone to their aunt's house on Cecil Avenue when bullets started flying outside during a block party. It was another drive-by. Nylah and another teenager were hit. Nylah did not survive.

Kennedy colors pictures to remember her sister as she tries to process the grief. Nylah’s mother, Candy Linear, said it has been a nightmare experience.

"Each day that I get up, some days, feels like a dream, feels like it didn't happen, or it's like I'm living in bad nightmare," Linear said. "To lose a child is like an out-of-body experience, because everything stops. It just stops. Your family is broken, and you can't fix it."

Linear keeps Nylah’s room just as she left it on the day she died, a load of laundry in the basket, her work clothes hung and all the mementos of a young girl who dreamed of working in fashion still in place.

"This pain in unimaginable and unending," she said. "I would wish it on no one."

Linear started a foundation in her daughter’s honor and name, hosting regular meetings for parents who lost a child. She said the crowd keeps growing, and there’s comfort in the common bond.

There are many similarities between the deaths of Tyree Smith and Nylah Linear. Both were 16 at the time of their death, both worked at local McDonald's restaurants, both of their moms kept their rooms just the same, both died in a drive-by shooting where neither were believed to be the target, and both cases remain unsolved.

"I'll never have justice no matter what happens, because they can't bring Nylah back," Linear said. "For me, that's justice."

16-year-old Nylah Linear, photo provided to WDRB News by Linear's mother.

LMPD reports show roughly 65% of the homicides in Louisville this year remain unsolved, far higher than the national average. The latest FBI reports show just less than 40% of homicides in the U.S. go without arrests.

“Until we can have a real honest conversation about where we are at as a city, things are not going to change,” said Kim Moore, executive director of Joshua Community Connectors, a nonprofit working with young adults trying to right their lives after incarceration.

“People are afraid to talk.”

Moore said she connects people with mental health services and assistance with basic needs like housing and employment. Her house sits on the same street in the Russell neighborhood where Tyree Smith died. Moore, 23 years sober, knows the neighborhood and the life well. As a member of the city's reentry task force, she's committed herself to rebuilding the streets she once called home.

“We have to talk about the breakdown of trust between police and the community," she said. "A lot things happen, and people don't want to call the police because they don't trust them, or if they come, somebody might get locked up. So we need to build a bridge with the community to have some cooperation with the police, because all police officers are not bad. But in light of the climate, you can see why people think like that.”

As the homicide rate increased, public trust in LMPD waned thanks to a series of high-profile scandals:

- 2016: Claims of sexual abuse in the Explorer youth mentoring program came to public light. City records revealed commanding officers knew of complaints at least two years earlier. Three officers were eventually convicted for sex crimes involving teenagers, and the city recently settled with the victims for $3.65 million.

- 2017: Both Louisville Metro Council and the LMPD union voted no confidence in then then-chief Steve Conrad. Mayor Greg Fischer refused to fire him.

- 2018: LMPD started the equivalent of stop and frisk in Louisville's high poverty, predominately Black communities. Conrad called it an attempt to get illegal guns and drugs off the street, but it saw people pulled from their cars, handcuffed and patted down for minor traffic violations. Lawsuits for harassment followed along with new traffic stop policies and the retraining of the entire police force.

- 2019: With mounting complaints against officers, LMPD started to let internal investigations linger. Not closing them keeps the files from being made public and those who complained from ever seeing a resolution. The department was slammed for lacking truthfulness, transparency and accountability.

All of that distrust exploded into more than six months of protests on the street with the police killing of Breonna Taylor. Two officers were fired, one quit and another was charged for what Taylor’s attorneys described as a botched raid.

The city settled with Taylor's family for $12 million, and the U.S. Department of Justice launched a federal investigation into LMPD. The department is now down about 300 officers with violent crime at an all-time high.

Moore said much of it centers on drugs.

"The (drug) game is lucrative right now, more lucrative than it's ever been," she said. "I work with kids whose family don’t want them to come out of the game. Why would you want him to come out if he's taking care of everybody? They're the bread winner."

She also believes retaliation is driving some of the gunfire.

"It's a lot of people who have clout in the streets," she said. And when they lose their life, a lot of people got to die behind them, and that's just the reality of it."

Cynthia and Delnicha Hall believe retaliation led to 9-year-old Larea Hall and her 8-year-old sister, Kanarri, being shot up in a car with their father, Larry Hall, behind the wheel.

"It was like 125 rounds," said Delnicha, Larry Hall’s sister. "It wasn’t fair."

The family said the victims were in no way part of the dispute. Cynthia Hall's home was shot up twice the night of Feb. 1. She said surveillance cameras captured the footage.

"It's breathtaking," she said. "You can't eat. You can't think. Your mind is just everywhere. Why would somebody do it? Who did it?"

The next day, Larry Hall and his two daughters were gunned down on Bells Lane near the Watterson Expressway. The family believes it was a revenge hit for a shooting two months earlier.

One of Larry Hall's relatives had killed a person who allegedly broke into his mother's home. There have been no charges in the case. The gunman claimed self-defense, but the family believes Larry, Larea and Canary Hall paid the price.

"Stop killing our babies," Larry Hall’s mother, Cynthia, said with conviction. "They ain't done nothing to nobody."

Only Kanarri survived the Feb. 2 shooting, and with no arrests in the case and shooters brazen enough to come back to her home several times and go after people not tied to the crime, Cynthia Hall said police told her to never go back home.

"Now, I had to bury my son and my grandbaby, and it hurts. And now, it's like I'm lost." she said. "You can't trust nobody, and I'm homeless. I was even sleeping in my car. It's an unexplainable feeling."

The stories show how a bullet hits one person and shatters the lives of the people and community around them.

"You traumatized everyone who was on this bus stop," Tyree Smith’s sister, Salena, said as her voice began to shake at at the corner where he was killed. “Most of us can't even walk to a bus stop no more because you took someone's life."

The remnants of a memorial sit at the corner now. Salena Smith was also on the way to school the day her brother was shot. She was feet from the gunfire.

"I don't understand it," she said. "Gun violence gets on my nerves! What is it about? I don't understand it. It makes me mad!"

Salena found comfort and a common bond meeting Nylah Linear's 15-year-old sister, Sakinah Abdul Jalil.

"Stuff that's too loud ... like I jump because of how close the bullets were," Sakinah said as she recalled the day her sister was gunned down at the family block party. "They were like flying past."

The trauma left Sakinah wrestling with depression and misplaced guilt.

"I'm angry that I didn't protect her," she said. "And I never realized how lonely I was until she got killed."

Louisville's scourge of violence is scarring a growing class of young people who've seen first-hand what most couldn't imagine. It's why Kilen and Cassandra Gray moved a Creative Spirits Behavioral Health office into west Louisville to serve where needed.

Kilen and Cassandra Gray moved a Creative Spirits Behavioral Health office into west Louisville to serve where needed.

"We do provide outpatient group therapy, expressive therapy, narrative therapy and cognitive behavior therapy so that they can find positive ways to express themselves," Cassandra Gray said.

Their offices are located on the same block where Tyree Smith was killed. The couple now offers a "huddle up" program and weekly group counseling free for the kids at the stop.

"The first thing is to create a safe space where trust can be built," Kilen Gray said when asked how to help a child who suffering from PTSD.

The couple’s treatment is based in faith. The Grays are both serving as interim pastors at First Baptist Church Jeffersontown. So while Sundays brings both pain and praise, their hope rests in a fitting scripture from Psalm 30:5:

And when you're in mourning, you pray for the light.

Copyright 2021 WDRB Media. All Rights Reserved.