LOUISVILLE, Ky. (WDRB) -- A Louisville woman died a slow painful death in the custody of the Jackson County Jail, crying out for hours until she was too weak to form words and the only sounds she could make were groans.

Ta'Neasha Chappell's death on July 16, 2021, brought protests, several investigations and national headlines as audio recordings and videos emerged showing her begging for help as her condition deteriorated over the course of 20 hours.

Now, three years later, in records newly obtained by WDRB News, some jail staffers admit they didn't believe she was critically ill. Our reporting is based on official public records of investigations, and judicial records, including sworn testimony given in a federal lawsuit.

"I don't think she was sick," Clayton Banister, a jail guard, said in an interview with an Indiana State Police investigator after Chappell's death. "She was responsive. I mean, it's hard to tell. Like, you don't know if they're faking it. ... But if she's responsive and looking at me and can walk, she's not sick."

Banister's interaction with Chappell happened around 10:30 a.m. July 16. Fellow inmates alerted guards that Chappell was laying on a floor in a dayroom. The 23-year-old was topless, covered in feces and wearing only her underwear. Banister's assessment of her illness was wrong. He escorted Chappell back to her cell with the help of another guard, Ryah Smith. Chappell was dead seven hours later.

It's one of several examples of the kind of care Chappell received behind bars in the final hours before her death. WDRB uncovered those examples when reviewing the ISP investigation previously withheld from the public, court records from the ongoing lawsuit and the depositions of jail staff questioned under oath about their response as Chappell was dying.

The material reveals several missteps and jail policy violations leading up to the end of her life.

"They knowingly did nothing and allowed someone to die," said attorney Sara Collins, who's representing Chappell's family in a lawsuit against Jackson County, which claims she was unreasonably denied medical care.

"It is extreme, extreme negligence," Collins said.

Chappell's pleas for medical care started long before she was laying on the ground covered in feces. Audio recordings confirm she told jail guards she was vomiting blood, needed help and needed to go to the hospital at least 20 times between 8 p.m. the night before and when EMS finally arrive around 3:30 p.m. the next day. Supervisors had to explain in depositions why her requests were not immediately acted upon.

Pictured: Ta'Neasha Chappell. Chappell died at a hospital in the custody of the jail in Jackson County, Ind., on July 16, 2021. (family photo)

"She kept saying she was vomiting blood, and the nurse said 'We needed to have evidence of the blood,'" Jackson County Jail Sgt. Scott Ferguson said in a deposition. "I said (to my staff) 'If you see blood in there, let me know right away.'"

While several guards responded to Chappell's cell, only one said he saw blood in her vomit: Seth Boyd.

"It was the last time I saw her," Boyd said in his deposition. "I saw the blood."

That was around 2:30 a.m. July 16. Boyd said he brought Chappell a bucket earlier in the night so she wouldn't have to keep getting out of her bunk when she was getting queasy. Boyd said he told Ferguson about the blood in her vomit, but Ferguson denied getting that information.

This discrepancy matters, as jail policy requires staff to call a doctor when an inmate vomits blood. They didn't. The jail contracts with Advanced Correctional Healthcare, Inc. — which has doctors available to call 24 hours a day — to guide inmates' medical care decisions.

Boyd also wrote in internal reports after Chappell's death that he saw she'd vomited blood. In his deposition, he said he wished she'd gotten to the hospital earlier. Instead, Boyd told Chappell "I spoke to the sergeant, and he said the nurse would see you in the morning."

Her death brought protests, several investigations and national headlines.

In depositions multiple jail staff members said they told their superiors about Chappell's deteriorating condition, but they did not directly notify the nurse.

Jail nurse Ed Rutan checked on Chappell at the start of his shift a little before 9 a.m. July 16, the day she died. Records show he took vitals and offered her Tylenol, saying she'd have a full medical visit in the afternoon. Chappell didn't make it to that full medical visit with Rutan. Thirty minutes after he left her cell, she was back on the talk box trying to get guards attention.

"I wasn't exactly sure what to do about it because I hadn't received any training yet," Smith said in a deposition when asked why she ignored Chappell.

Chappell called at 9:20 a.m., reporting that she had vomited in her sleep. Smith responded saying "all-righty," after which she hung up but failed to tell the jail nurse or any supervisor, according to court records.

Smith was also manning the guard station when Chappell repeated "I need help" nine times in a row over the course of a minute with agony in her voice. No one responded. When pressed on why she "ignored" Chappell in her deposition, Smith replied, "I'm not 100% sure why."

As Chappell's cries grew weaker in the early afternoon, she started becoming incoherent and her moans unintelligible.

Jail staff eventually moved her to a room for monitoring. Naked, wobbling and fading, she fell and hit her head on the bunk. This is when they finally acknowledged she needed medical care. It's 2:30 p.m., but she laid on the ground 40 more minutes as the nurse wouldn't go in the cell.

"I didn't realize she wasn't able to dress herself," Rutan said. "(There's a) possibility of accusation. Not going to enter if she don't have any clothes on. I'm not going to go into the cell by myself."

He sent two female guards in, but they didn't help her get dressed either.

"This is just making us think that you're faking it," guard Tammy Baxter said to Chappell as she laid curled in a ball on the floor of her cell, naked and unable to get dressed. "So if you don't get up and get dressed, we're going to leave you alone, and you can sit there and just suffer."

And suffer Chappell did.

Jackson County Jail in Indiana.

When EMS finally arrived, Chappell propped herself up on a wall, staggered to the gurney and fell. No one helped her. She was dead at Schneck Medical Center two hours later: 5:42 p.m. July 16, 20 hours after she first called for help.

"There is no peace. There is no making comfort with this," Chappell's sister, Ronesha Murrell, said in an interview with WDRB News as she wiped tears from face. "It was hours of her begging and pleading, slowly just losing who she is. ... I feel like none of them did what they were supposed to do."

"They were evil," said Lavita McClain, Chappell's mother. "They treated her like she was a dog."

Police arrested Chappell in May 2021 for shoplifting and a miles-long police chase that started at the outlet mall in Columbus, Indiana, and ended in a crash on Interstate 65 in Clark County.

Loved ones said it's a heavy load to live under the weight of no resolution.

How Did She Die?

Investigative records revealed competing theories on what killed Chappell. The medical examiner ruled it "probable toxicity" with a manner undetermined. Rumors in lockup said she was poisoned. Forensic Pathologist Dr. Latajna Watkins found a green liquid in her abdomen, but lab tests couldn't confirm it.

"If there was an unknown, undetected toxic substance ingested, it may not be detectable by toxicology," the state police report stated.

The other theory came from Dr. Frank Pangallo, the emergency room doctor who treated Chappell at Schneck Medical Center. Pangallo initially thought Chappell died of toxicity and treated her as if she'd ingested antifreeze. But investigative records reveal his change of theory.

"If it wasn't a toxic ingestion, then I think she was suffering from Sickle Cell, and Sickle Cell disease can give you all kinds of weird symptoms that, to the uninitiated, might appear to be either contrived or trivial," Pangallo said to the state police investigator. "It can cause body aches, belly pain (and) headaches. It can cause heart attacks. It can do a lot of stuff and, if it's allowed to go on for a period of time, you can get like this. So I think what we were seeing was the end result of prolonged Sickle Crisis."

Previous medical records say Chappell had Sickle Cell, and Rutan admitted she'd told him that during his brief visit the morning she died. Other jail staff members didn't have information about her pre-existing conditions, because the required medical questionnaire when she was first booked into jail was not done. Rutan also failed to do the 14-day follow-up medical intake.

"It would have been different if I knew her medical history," Ferguson said.

A third theory emerged in court records from medical experts hired by Chapell's family and the county. Dr. Louis Profeta, hired on behalf of the Chappell estate, and Dr. Kerry Cleveland, hired by Jackson County, both agreed Chappell likely died from sepsis due to an infection. They did not see eye to eye on the impact of Chappell's wait to get to the emergency room.

While Dr. Pofeta said every minute delayed decreased her chance of survival Dr. Cleveland said no physician could be certain earlier care would have prevented Chapell's death.

"No answers with no justice is the worst feeling ever," Murrell said. "No one wants to take the fall for it."

The prosecutor in Jackson County never brought findings to a grand jury to consider if jail staff broke the law.

"No crimes were committed by the Jackson County Jail related to the death of Ta'Neasha Chappell," Prosecutor Jeff Chalfant wrote in a 2021 news release explaining his decision. "Whether a person or entity had a duty of reasonable care are matters of civil law and not criminal law."

A civil court has already found at least one of the guards, Smith, acted unreasonably. Court records show she not only ignored Chappell in one of her calls for help, but, after she took Chappell back to her cell with Banister, she failed to start a medical watch checking on Chappell every 15 minutes as instructed by a supervisor.

"No reasonable juror could conclude from the evidence of these encounters that Officer Smith acted reasonably in response to Ms. Chappell's serious medical need," U.S. District Court Judge Sarah Evans Barker wrote in her opinion granting summary judgment to Chappell's estate. "Officer Smith's relative inexperience and lack of formal training do not excuse her failures to contact her supervisor or the jail nurse to report Ms. Chappell's deteriorating condition."

The ruling means Smith violated Chappell's 14th amendment right to medical care, and the question now is how much will the county have to pay for it.

Smith, 12 other jail staffers and Jackson County Sheriff Rick Meyer are all named in the lawsuit. The attorney for the group did not return a request for comment in the investigation. The county's legal team has attempted to get the suit dismissed on several grounds, including qualified immunity. Those efforts were mostly unsuccessful. However, three jail employees have been dismissed from the case.

Tammy Baxter and Wendy Boshears were the two women sent into Chappell's cell to help her get dressed before EMS arrived. But Baxter and Boshears were dismissed from the case due that timing. Boshears told Chappell when the two female guards went in the cell around 3 p.m. July 16 that she thought Chappell was faking as she laid riving on the floor. But Chappell was already 18 hours into her distress, and an ambulance arrived within 30 minutes.

"Beyond Officer Baxter's callous statements to Ms. Chappell, the undisputed evidence reveals that neither officer had any direct involvement in delaying or denying Ms. Chappell access to medical care," Barker wrote.

Jail Lt. David Ridlen is also no longer a part of the legal proceedings. Court records show his involvement was limited to ordering Banister and Smith to start a medical watch on Chappell. They didn't, but his order satisfied Baker enough to determine that his response was reasonable.

"There are serious problems at that jail, and, if things don't change, more lives will be lost," Collins warned.

More Lives Were Lost

Two other inmates have died in the custody of the Jackson County Jail. One of them, Joshua McLemore, died in custody just three weeks later.

Reports say the schizophrenic man was suffering a psychotic break at the time of his arrest in August 2021. The jail locked him in solitary confinement. He was naked for 20 days and lost 45 pounds as he refused to eat. Records show, much like Chappell, he received no medical care until it was too late. The medical examiner noted multiple organ failures due to malnourishment with an altered mental status due to untreated schizophrenia as the cause of death. Last year, Jackson County settled with McLemore's family for $7 million.

A second in-custody death that raises potential concerns is that of 35-year-old Antonio Fox. Initial reports from ISP said the Jackson, Mississippi, man collapsed in his cell April 23, 2024, while corrections officers were checking on him. Similarly to Chappell, he died shortly after arriving at Schenck Medical Center. The state police investigation into his death has not been released.

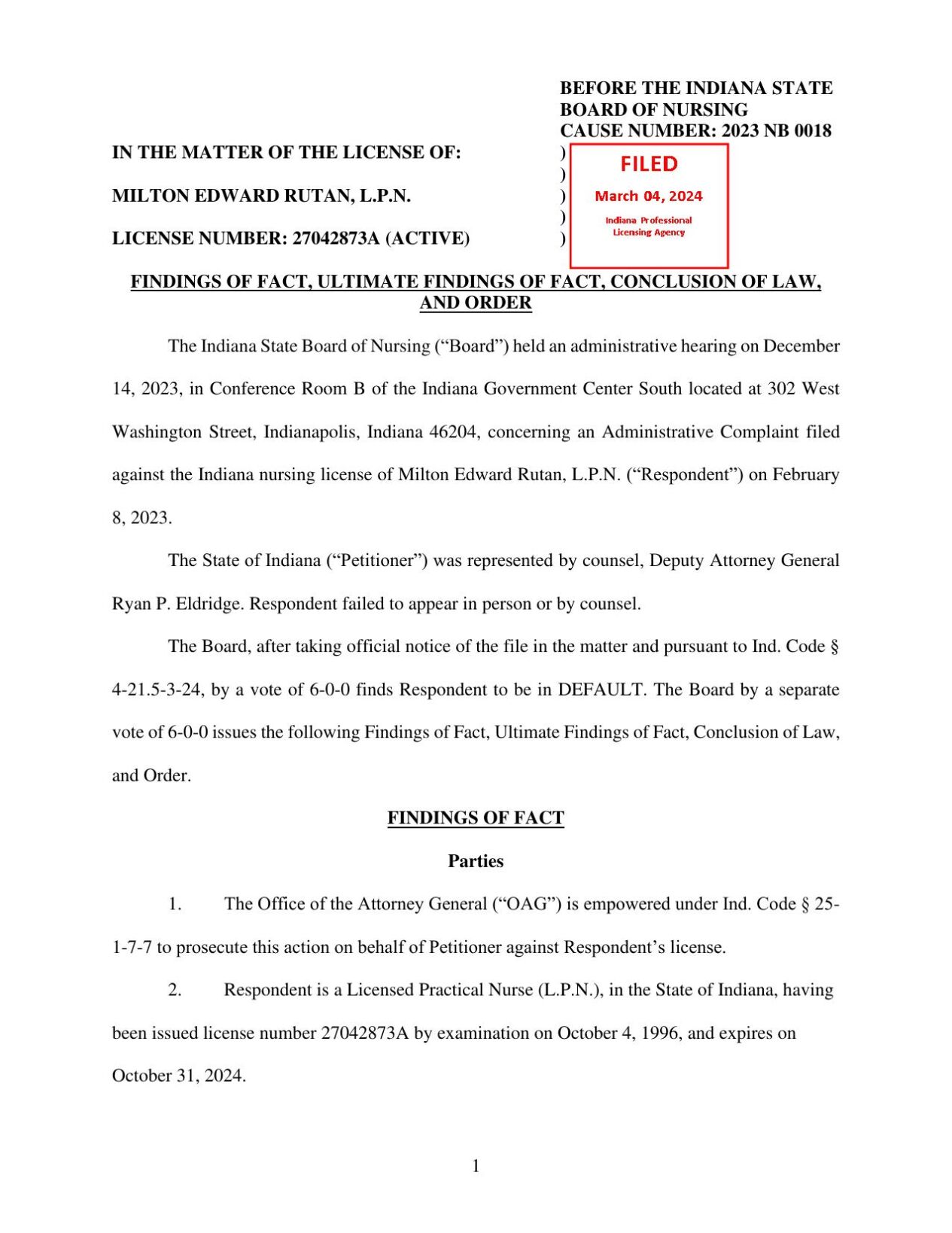

The combination of Chappell's passing and McLemore's weeks later ultimately cost Rutan his career. The Indiana Board of Nursing revoked his license citing professional incompetence, unsafe judgment and abandonment or neglect among a list of reasons.

It is not the accountability Chappell's family is seeking. They're calling for federal investigators to step in to give Chappell the help she didn't get behind bars.

"I want whoever didn't do anything for my daughter to be held responsible and I want the FBI to get involved," McClain said.

"We want criminal charges," Murrell said. "My sister should still be here."

Ta'Neasha Chappell's death on July 16, 2021, brought protests, several investigations and national headlines as audio recordings and videos emerged showing her begging for help as her condition deteriorated over the course of 20 hours.

Ta'Neasha Chappell Coverage:

- 'I need help': Audio reveals slow, painful death for Louisville mother in custody of southern Indiana jail

- After seeing toxicology report, family of Louisville woman who died in jail custody plans rally

- Family of Jackson County inmate who died in custody files lawsuit against jail workers

- Investigation: Louisville woman 'suffered' before death in Indiana jail custody