LOUISVILLE, Ky. (WDRB) — This is a column I told myself I would not write again. If the first 811 versions did not make a difference, what was the purpose of one more.

Then, on Thursday, word leaked that the National Football Foundation made an adjustment to its eligibility requirements for the College Football Hall of Fame.

Gone was the requirement for a career winning percentage of .600. That number got a tiny tweak, dialed down to .595.

Social media was packed with celebration. This change should clear the path for Mike Leach, Jackie Sherrill and Les Miles.

I wish nothing but the best for the inclusion of those three men. Fine coaches, all of them.

But this isn’t about them. This is about another coach who deserved his moment of enshrinement long, long ago.

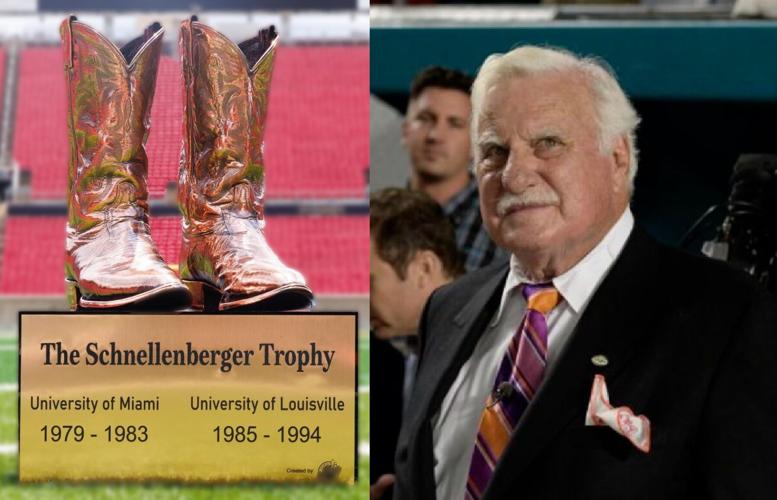

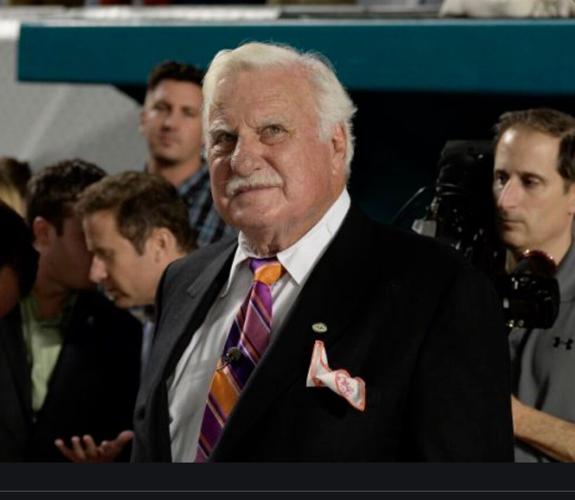

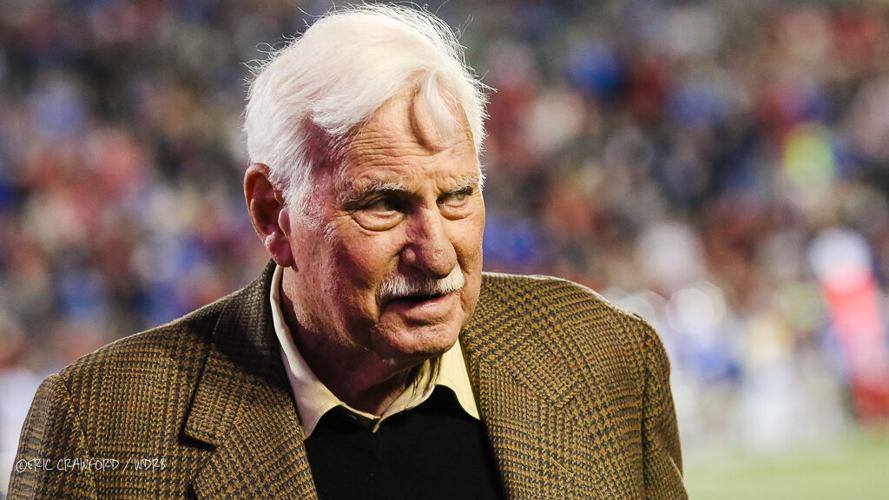

That coach is University of Louisville legend Howard Schnellenberger.

Who has a national title.

Who never lost a bowl game.

Who grabbed the wheel of a floundering Miami Hurricanes’ program that was tracking toward irrelevance (or worse) and placed it on collision course toward establishing itself as a national force and brand.

Who accepted the challenge of rescuing a Louisville program that was considering relegation to Division I-AA status and got U of L rolling on its way to a program that has won the Fiesta, Orange and Sugar bowls, while constructing a new stadium and producing a Heisman Trophy winner.

Who, in his final act, created a solid FBS program at Florida Atlantic, merely through a force of his indomitable will.

Yes, Howard Schnellenberger’s career winning percentage is .514, below Leach (.596), Miles (.597), Sherrill (.595) and the new HOF standard.

I’ll say it again. I’m not here to compare Schnellenberger to those three coaches, who all achieved great things.

Leach, once an assistant to Hal Mumme at Kentucky, changed college football by spreading the popularity of the Air Raid offense. If you weren’t passing the ball at least 40 times a game, you weren’t trying.

Leach showed he could win at Texas Tech, Washington State and Mississippi State, programs that have never been compared to Oklahoma, USC and Alabama.

Miles earned a national title at Louisiana State. His LSU teams won 10 or more games seven times in 12 seasons in Baton Rouge.

Sherrill went 33-3 during a three-season stretch at Pittsburgh, before finishing his 26-season head coaching career at Texas A&M and Mississippi State.

No complaints from me if Leach, Miles or Sherrill have their moment.

But I do have a complaint about the exclusion of Schnellenberger, who, for the record, was also an all-American receiver at Kentucky and top assistant coach to Bear Bryant at Alabama.

If the National Football Foundation can adjust its rules to accommodate the inclusion of coaches who were one or two victories shy under the 60% winning percentage rule, why can’t the NFF consider the backdrop of the challenges Schnellenberger accepted and overcame.

It’s not a borderline case. Howard Schnellenberger changed the course of college football at three different places.

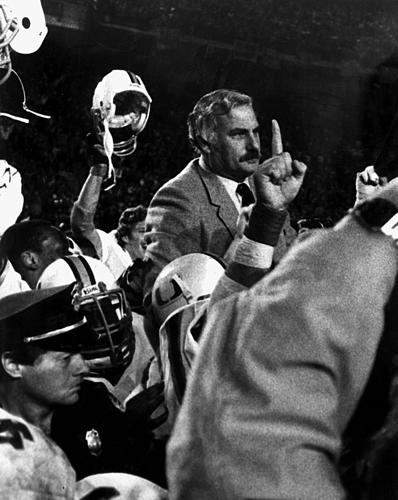

The national championship that Schnellenberger’s 1983 Miami team won over Nebraska in the Orange Bowl is considered one of the greatest upsets in the game.

Sports Illustrated wondered if the unbeaten, top-ranked Cornhuskers were the greatest team ever.

Schnellenberger answered the question with a firm “No.” Not only did Miami cover the 10 1/2-point spread, the Hurricanes beat Nebraska, 31-30.

That was the first of five national titles Miami won over the next two decades. Although Schnellenberger only won the first before he erred by taking a job in the USFL, he set it up for Jimmy Johnson, Dennis Erickson and Larry Coker to succeed.

He won better than 71% of his games there. Nobody questions that he would have won more national titles if he stayed in South Florida.

That was not the Schnellenberger Way. His indomitable spirit was driven by accepting challenges that made other coaches flinch.

The primary reason he is not eligible for the Hall of Fame is that Schnellenberger won 49.1% of his games in 10 years at Louisville and 42.3% in eight seasons at FAU. (Those two runs sandwiched a single 5-5-1 performance when he made the mistake of leaving Louisville for Oklahoma in 1995. Career management was not one of his strengths.)

But you don’t have to call in Woodward & Bernstein to grasp the rest of the story.

At Louisville, he stirred the university into building a stadium that the school has twice expanded. He scheduled anybody willing to play him, giving U of L the national credibility to make its move to Conference USA, the Big East, the American Athletic Conference and now the Atlantic Coast Conference.

He was willing to play four consecutive games in Lexington to ensure the launch of the Governor’s Cup rivalry with Kentucky. He beat Alabama in the Fiesta Bowl and Michigan State in the Liberty Bowl during a era when a program needed more than a pulse to qualify for a bowl game.

That’s plenty of material for a Hall of Fame plaque, but if you need more, remember that Schnellenberger created the program at Florida Atlantic, including the construction of a 30,000-seat football stadium.

He also won a pair of bowl games at FAU, bumping his career bowl record to 6-0.

I could write more. Much more. But I said I wasn’t going to write another Howard Schnellenberger belongs in the College Football Hall of Fame column.

Then the National Football Foundation did something that required me to do it. If the NFF can change its eligibility rules, it can create a path for Schnellenberger to earn the recognition he clearly earned.

Other Sports Stories:

Earl Clark to make much-anticipated TBT debut with Louisville alumni team

BOZICH | Readers respond to Louisville-Indianapolis sports town debate

CRAWFORD | Welcome to the college football oligarchy -- Greg Sankey is helping to build it

Copyright 2025 WDRB Media. All rights reserved.