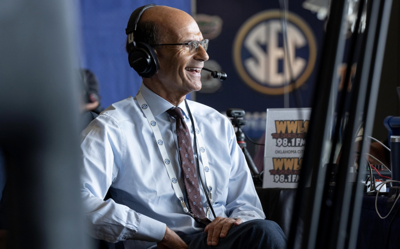

LOUISVILLE, Ky. (WDRB) – Paul Finebaum might run for U.S. Senate.

That’s not a punchline. According to reports, the longtime voice of SEC football — part broadcaster, part therapist for Southern college fans — is seriously considering entering the Alabama Senate race.

He would be seeking the seat currently held by former Auburn coach Tommy Tuberville, who is planning a run for governor. That same seat drew interest from retiring Auburn basketball coach Bruce Pearl.

Don’t they know? The person with the most experience angling for a seat held by Tuberville is Bobby Petrino. (Sorry. Deep cut. Couldn’t help it.)

My larger point is this: sports personalities are pouring into the political landscape, and not just as endorsers or influencers — as actual candidates.

The athlete-to-politician pipeline

Former Tennessee Titan Colin Allred is running for U.S. Senate in Texas. Dodgers legend Steve Garvey ran for Senate in California. Danica Patrick has floated a House run in Arizona. Herschel Walker, one of the most iconic college football players of all time, tried to win a Senate seat in Georgia.

This isn’t new.

Bill Bradley parlayed a Hall of Fame NBA career with the New York Knicks into three terms in the U.S. Senate — and a serious presidential run. Jack Kemp went from Buffalo Bills quarterback to congressman, cabinet member, and vice-presidential nominee. Jim Bunning pitched his way into Cooperstown and then into Congress, eventually serving two terms in the U.S. Senate from Kentucky.

Arnold Schwarzenegger turned bodybuilding into movie stardom, and stardom into the governorship of California. Vitali Klitschko — a former heavyweight boxing champion — has been mayor of Kyiv since 2014. George Weah, a Ballon d'Or–winning soccer legend and FIFA World Player of the Year, is the president of Liberia.

In some cases, the leap is obvious: public figure becomes public servant. But in others, it’s more of a Hail Mary.

Richie Farmer, the beloved Kentucky basketball icon, was elected agriculture commissioner — and later convicted on corruption charges. Walker, despite strong polling, couldn’t win in Georgia. Jim Tressel, the former Ohio State football coach, is now lieutenant governor in Ohio, navigating a far more bureaucratic field than third-and-long.

What sports does prepare you for

Athletes learn discipline, leadership under pressure, and how to operate under intense public scrutiny. Many become skilled communicators — or at least, comfortable in front of cameras.

They understand preparation. They understand failure. They understand what it means to perform when the moment demands it. And in a fractured media landscape, the visibility that sports provides can be a candidate’s biggest early asset.

There’s also an aspirational pull. Voters like candidates who “won” something. Who sacrificed. Who competed. Who succeeded on a national stage.

It’s no accident that Teddy Roosevelt — one of our youngest and most physically robust presidents — revolutionized the sport of football while in office. After overcoming childhood illness through physical activity, he later instituted safety standards and helped found the organization that became the NCAA.

What sports doesn’t teach you

But here’s the other side of the medal.

Winning votes isn’t like winning games. It’s not about execution in the moment — it’s about long-haul planning, policy knowledge, diplomacy, and compromise. And fundraising. Lots of fundraising. There are no referees. There’s little way to stay on the sidelines.

The qualities that make athletes successful — self-belief, combativeness, charisma — can become liabilities when applied without reflection to the messier, slower world of governance.

Sports teaches you to dominate. Politics requires you to negotiate.

In the SEC, Paul Finebaum is a heavyweight. On Capitol Hill, he’d be a freshman. And that’s not a knock — it’s just the difference between broadcasting and bill-writing.

Conclusion: A starting block, not a shortcut

So yes, the athlete-to-politician trend is real. And yes, it makes a certain kind of sense. Sports offers a ready-made platform and an audience that trusts you, or at least knows your name.

But name recognition isn’t the same as readiness. It’s the coin you pay to get in the race, not the currency that helps you win it. You might be able to run the ball. But if you’re not legitimately inspiring in front of an audience that cares more about what you can do for them than what you did on the field, victory can be a tougher proposition.

And frankly, that’s how it should be.

You can run for office on a winning reputation. But if you can’t explain what you’d do once in office — and how you’d do it — voters eventually move on to the next candidate.

That’s not a bad thing. It’s just democracy in regulation time.

It’s why I don’t think we’re heading for an athlete-ocracy anytime soon. No matter how many of them jump into the ring.

Quick Sips

FUN FACT: Georgia, which is Kentucky’s opponent on noon Saturday, has not covered in a single game this season. That, and other valuable information, is available in my nuts-and-bolts preview. You can read it here.

SHOWTIME IN BLOOMINGTON: When I suggested to some Indiana basketball players that their entirely rebuilt roster had kind of a reality-show feel on Tuesday, they didn’t disagree. Read more about what first-year coach Darian DeVries is trying to pull off in one of basketball most storied programs in my column here.

The Last Drop

“Alabama has always been the place I've felt the most welcome, that I've cared the most about the people. I've spoken to people from Alabama for 35 years, and I feel there is a connection that is hard to explain.”

SEC Network host Paul Finebaum, to radio host Clay Travis

Copyright 2025 WDRB Media. All Rights Reserved.