LOUISVILLE, Ky. (WDRB) – “There is no hunting like the hunting of man and those who have hunted armed men long enough and liked it, never really care for anything else thereafter…”

The quote, from Ernest Hemingway in a 1936 Esquire magazine piece, appeared on the cover of a training course on executing search warrants used by the Louisville Metro Police Department.

Louisville police have since removed the words from the training manual, calling them “completely inappropriate.”

But a recent court filing has brought scrutiny to the quote and images in the training materials, including a picture of a bloody Black man who appears to be dead as well as a cartoonish gang member shooting a gun alongside images of drugs and money.

The training materials were filed in an ongoing lawsuit accusing at least 10 SWAT officers of raiding a vacant home to serve a search warrant on a drug suspect – only to handcuff a house painter, his girlfriend and her 11-year-old daughter.

Attorney Josh Rose, who represents painter Roy Stucker and his family, wrote in a court filing that the cover of the training materials “seems to promote portraying citizens as the enemy and not worthy of constitutional protection.”

The front page of the training material.

Rose said in an interview this week that he was “shocked” by the language and images.

“The police are there to protect and serve, not to hunt anyone,” he said. “To me, it fosters a culture of an us versus them mentality that the people they are supposed to protect and serve are the enemy.”

The suit alleges the target of the raid had been selling drugs at other locations for several weeks prior without even going to the home police raided, which he had visited just twice in previous months. In fact, he had already been arrested earlier in the day before the raid, according to the suit.

The Hemingway quote has previously come under scrutiny after use by police elsewhere.

Members of the New York City Police’s Warrant Squad, for example, were criticized several years ago for wearing shirts with the quote on the back.

It was also put on the wall of a Brooklyn police precinct house.

In an article by the Gothamist earlier this year, the NYPD deputy commissioner said the Hemingway quote should not be seen as threatening, but as a tribute to the fearlessness of local officers tracking down “violent felons whose victims are members of that community.”

In addition to the quote, Rose said the pictures of a bloody man and cartoon of a “stereotypical gang-banger,” as well as images of large amounts of cash and drugs, were “concerning to me because you are portraying that every search warrant, you are engaging in some type of war with the public.

Attorney Josh Rose (WDRB photo).

"That’s not conducive to protecting citizens constitutional rights.”

‘Completely inappropriate’

In a statement to WDRB News, a police department spokeswoman said the training class was taught by someone outside the department and “the quote and pictures were removed from the curriculum about a year ago after LMPD’s Training staff requested the instructor take out that portion.”

LMPD, according to the statement from Alicia Smiley, “finds this quote to be completely inappropriate which is why it is no longer a part of our training materials.”

When pressed for exactly when the materials were removed and how long they were used to teach LMPD officers, Smiley said they were taken out in 2019 but declined to comment further.

Rose said he requested the training materials from the city after filing the lawsuit in November 2019 and didn’t receive them until the middle of 2020. He said he has not received any other search warrant training materials from the city.

The search warrant class has been taught by retired LMPD Ofc. Michael Halbleib since around 2012, according to a deposition in court records of an LMPD sergeant in the training division.

Halbleib, now a major with the Bullitt County Sheriff’s Office, said in an interview he doesn’t believe he is still using the cover with the Hemingway quote and pictures.

Asked if the quote and pictures were appropriate, Halbleib said he would have to ask his supervisors if he was allowed to comment. He did not call back.

The so-called “warrior mindset” in police training has become a controversial issue for many departments and mentioned in lawsuits across the country in recent years.

In Kentucky, an October 2020 report from student journalists at Louisville’s duPont Manual High School revealed training materials used by Kentucky State Police included quotes from Adolf Hitler and advocated for “ruthless” violence.

An online course for recruits training to be police officers across the state included an image from a website called Nappyafro.com and used the term “Gorilla Pimp” next to a picture of a shirtless Black man in a section on human trafficking, according to documents in a 2021 whistleblower lawsuit.

The slides, which included several pictures of Black people in the trafficking section were called “derogatory and racist” by some former employees of the state’s Department of Criminal Justice. The lawsuit is pending.

A recent review of LMPD by Chicago-based Hillard Heintze found that search warrant training was not mandatory, and the department could not determine what percentage of officers have elected to take the course.

However, the city reported in the Stucker lawsuit that between 2018 and 2019, less than six percent of LMPD’s officers took the search warrant training.

The search warrant training class is still not mandatory, Smiley said in an email. And she added that the department is working to review "all lesson plans for content."

The Hillard Heintze work also found a “culture of acceptance” within LMPD in which “supervisors seldom queried officers regarding the underlying facts and circumstances necessary to demonstrate probable cause.”

Rose wrote in court records that there is a “custom, culture and tolerance” in Louisville for officers to obtain search warrants without probable cause.

The detective who obtained the search warrant in the Stucker case acknowledged he hadn’t been required to take the training until January 2021, or about 18 months after the raid.

“Most of what I’ve learned has been from experience and other fellow detectives,” Det. Wesley Troutman said in a deposition.

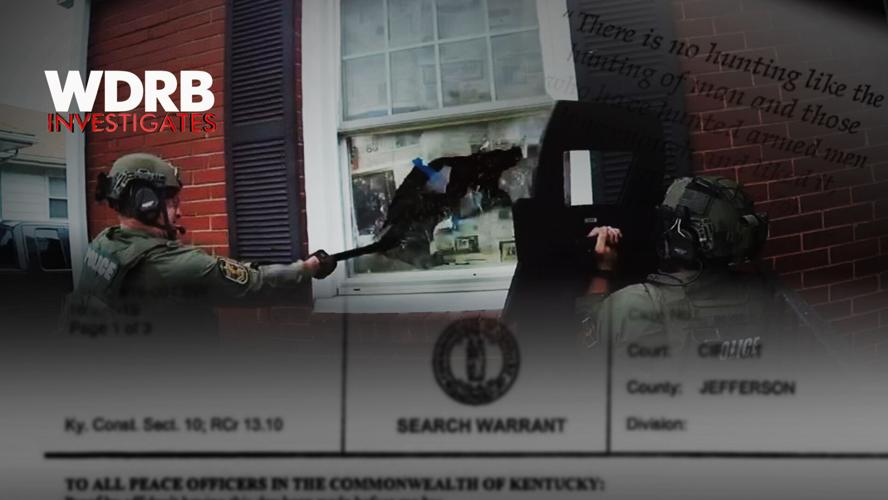

In the Stucker case, police can be seen breaking through the doors and windows of the rental house near Louisville Muhammad Ali International Airport, assault rifles drawn on July 15, 2019, according to body camera video.

Video of the SWAT raid at center of lawsuit by Roy Stucker for a 2019 raid by Louisville Metro Police. Stucker, his girlfriend and 10-year-old daughter were put in handcuffs.

Stucker, his girlfriend and her 11-year-old daughter were handcuffed for about 30 minutes.

Stucker had been hired by the owner of the property to paint the home and was on his second day.

The search warrant, obtained by Troutman, had “stale and insufficient information” and was not properly reviewed by the appropriate people in the department before it was submitted to and signed by a judge, Rose wrote in court documents.

Officers failed to “even bother to determine who lived in the residence,” he wrote.

In his deposition for the lawsuit, Troutman said he tried to determine who lived in the house but “never was successful.”

“Police had no idea who actually lived in the residence, even before it was vacated,” Rose said in an interview. “And they had no idea it had even been vacated for at least a week.”

City defends raid

The recent filings by Rose also argued that LMPD failed to change its methods after other botched search warrants.

“It’s been a trend leading up to the Breonna Taylor incident,” Rose said of the March 13, 2020 raid in which officers shot and killed Taylor inside her apartment near Pleasure Ridge Park.

The city paid $12 million to the Taylor family and enacted numerous reforms to settle a wrongful death lawsuit six months after the 26-year-old was shot.

More recently, the city paid $460,000 to a Louisville couple and their three children earlier this year to settle a 2019 lawsuit claiming 14 SWAT officers erred in raiding their home, smashing through the front door, using explosive devices and holding the family at gunpoint.

“Like in this matter, the officer … used stale information, did not determine who lived in the residence and failed to take the Search Warrant Training,” Rose wrote in a court filing.

Besides information from a confidential informant, an LMPD detective claimed he smelled marijuana coming from outside the West Chestnut Street home on separate occasions and believed someone was growing and selling marijuana inside, according to a search warrant.

The man and woman named in the search warrant affidavit and described as growing and selling marijuana did not live at the home – information that could have easily been discovered by police, according to the suit.

The settlement agreement stipulated that the city did not admit fault and both sides settled to “avoid the expenses and uncertainty of continued litigation” in a disputed claim.”

No officers in that raid or the Stucker case have been punished, Rose said.

“In fact, there was not even an internal investigation to determine if officers should be disciplined,” he said. “It seems to condone a culture of acceptance.”

Meanwhile, the city is defending actions by LMPD officers in the Stucker case.

In a motion to dismiss the lawsuit last month, Metro attorneys argued that Troutman’s search warrant request was approved by Jefferson Circuit Court Judge Mary Shaw, who found there was sufficient evidence for the warrant.

An attorney for the city also noted that the suspect later admitted he had previously picked up drugs from the house, and he claimed Stucker and his family failed to open the door for the SWAT offices in a reasonable amount of time.

“The residence windows were plastered with newspapers that obstructed the view into the residence,” Assistant Jefferson County Attorney John Carroll wrote. “A proper break and rake of two windows was conducted by the SWAT officers under the circumstances present.”

Rose said in an interview it is disappointing but not surprising that the city continues to deny any wrongdoing.

“Unfortunately (the city) has not in any way apologized or recognized that something went wrong,” Rose said. ”It takes a lot of time and effort to change culture.”