In case you missed it yesterday, Yellowstone National Park experienced a small hydrothermal explosion in the Biscuit Basin thermal area, about 2.1 miles (3.5 km) northwest of Old Faithful. Here's more on what USGS had to say about the event:

Image Credit: Yellowstone National Park

At around 10:00 AM MST on July 23, 2024, a small hydrothermal explosion occurred in Yellowstone National Park in the Biscuit Basin thermal area, about 2.1 miles (3.5 km) northwest of Old Faithful. Numerous videos of the event were recorded by visitors. The boardwalk was damaged, but there were no reports of injury. The explosion appears to have originated near Black Diamond Pool.

Biscuit Basin, including the parking lot and boardwalks, are temporary closed for visitor safety. The Grand Loop road remains open. Yellowstone National Park geologists are investigating the event.

Hydrothermal explosions occur when water suddenly flashes to steam underground, and they are relatively common in Yellowstone. For example, Porkchop Geyser, in Norris Geyser Basin, experienced an explosion in 1989, and a small event in Norris Geyser Basin was recorded by monitoring equipment on April 15, 2024. An explosion similar to that of today also occurred in Biscuit Basin on May 17, 2009.

Monitoring data show no changes in the Yellowstone region. Today’s explosion does not reflect activity within volcanic system, which remains at normal background levels of activity. Hydrothermal explosions like that of today are not a sign of impending volcanic eruptions, and they are not caused by magma rising towards the surface.

Additional information will be provided as it becomes available.

The Yellowstone Volcano Observatory (YVO) provides long-term monitoring of volcanic and earthquake activity in the Yellowstone National Park region. Yellowstone is the site of the largest and most diverse collection of natural thermal features in the world and the first National Park. YVO is one of the five USGS Volcano Observatories that monitor volcanoes within the United States for science and public safety.

YVO Member agencies: USGS, Yellowstone National Park, University of Utah, University of Wyoming, Montana State University, UNAVCO, Inc., Wyoming State Geological Survey, Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology, Idaho Geological Survey

Image Credit: Yellowstone National Park

Hydrothermal Explosions

Image Credit: USGS

You may have read that and said to yourself "what in the world is a hydrothermal explosion". Well, let's answer that with an explanation from the USGS.

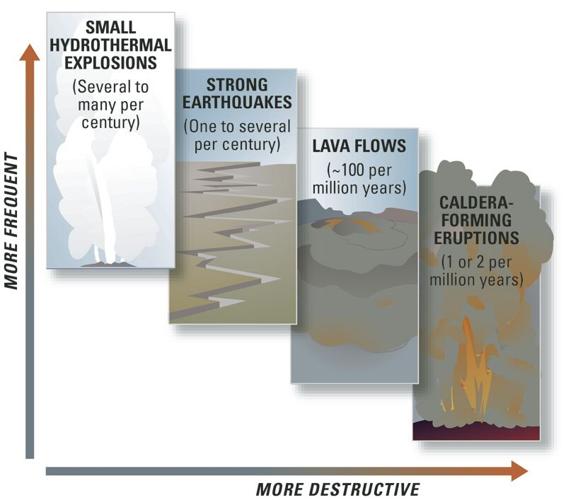

Most people mean the big explosion, but that's not a particularly likely event. In fact, most people do not know about the potential hazard associated with a hydrothermal (hot water) explosion, which is far more common than any eruption of lava or volcanic ash.

Hydrothermal explosions are violent and dramatic events resulting in the rapid ejection of boiling water, steam, mud, and rock fragments. The explosions can reach heights of 2 km (1.2 miles) and leave craters that are from a few meters (tens of feet) up to more than 2 km (1.2 mi) in diameter. Ejected material, mostly breccia (angular rocks cemented by clay), can be found far as 3 to 4 km (1.8 to 2.5 mi) from the largest craters.

Hydrothermal explosions occur where shallow interconnected reservoirs of fluids with temperatures at or near the boiling point underlie thermal fields. These fluids can rapidly transition to steam if the pressure suddenly drops. Since vapor molecules take up much more space than liquid molecules, the transition to steam results in significant expansion and blows apart surrounding rocks and ejects debris. Hydrothermal explosions are a potentially significant local hazard and can damage or even destroy thermal features. In Yellowstone, hydrothermal explosions occur within the Yellowstone Caldera and along the active Norris-Mammoth tectonic corridor.

Large hydrothermal explosions occur on average every 700 years, and at least 25 explosion craters greater than 100 m (328 ft) wide have been identified. The scale of these craters dwarfs similar features in geothermal areas elsewhere in the world. Large hydrothermal explosions in Yellowstone occurred after an icecap greater than 1 km (0.6 mi) thick receded from the Yellowstone Plateau around 14,000-16,000 years ago.

Hydrothermal explosion at Biscuit Basin in Yellowstone National Park. These types of events are the most likely explosive hazard from the Yellowstone Volcano.

Image credit: USGS

Studies of large hydrothermal explosion events in Yellowstone indicate: (1) none are directly associated with magma; (2) several smaller historic explosions have been triggered by seismic events, like the 1959 Hebgen Lake earthquake; (3) rocks ejected by hydrothermal explosions show significant mineral alteration, indicating that explosions occur in areas subjected to intense hydrothermal processes; and (4) many large hydrothermal explosion craters in Yellowstone are similar in area to active geyser basins and thermal areas.

Critical components for development of large hydrothermal systems require high heat flow, abundant water (Yellowstone Plateau receives about 180 cm (70 in) of precipitation annually), and seismicity (Yellowstone experiences 1000-3000 earthquakes/year) to maintain open fractures. Active deformation of the Yellowstone Caldera and seasonal changes also contribute.

Hydrothermal systems with explosive potential have a water-saturated system at or near boiling temperatures and an interconnected system of well-developed joints and fractures along which hydrothermal fluids flow. Ascending hydrothermal fluids flow along fractures that have developed due to repeated inflation and deflation of the caldera, which causes rocks to break, and along edges of low-permeability rhyolitic lava flows. The size and location of hydrothermal fields may be limited by excessive alteration of rocks and development of clay minerals that can create caprocks and seal the system. If a portion of the system is sealed, any sudden or abrupt drop in pressure causes water to flash to steam, which is rapidly transmitted through interconnected fractures. The result is a series of multiple explosions and the excavation of a crater. Similarities between the size and dimensions of large hydrothermal explosion craters and thermal fields in Yellowstone indicate that this type of event may be an end stage in geyser basin evolution.

Aerial photo of the 0.06 square mile (0.16 square kilometer) Indian Pond hydrothermal explosion crater north of Yellowstone Lake. The deposits from the explosion that formed the crater were dated with radiocarbon to 2,900 years ago. Photo from Yellowstone National Park Photo Collection taken by Jim Peaco in July 2001.

Image Credit: USGS

Although large hydrothermal explosions are rare events on a human time scale, the potential for additional future events of the sort in Yellowstone National Park is not insignificant. Based on the occurrence of large hydrothermal explosion events over the past 16,000 years, an explosion large enough to create a 100-m- (328-ft-) wide crater might be expected every few hundred years.