LOUISVILLE, Ky. (WDRB) — When Campari Group announced its $420 million deal to buy a controlling stake in Wilderness Trail Distillery last year, the Italian liquor giant said the Kentucky distillery would provide much-needed juice for its expansion into premium bourbon — particularly, Campari’s “highly profitable” but supply-starved “Whiskey Barons” expressions.

There was only one problem.

A portion of the output of the 10-year-old Wilderness Trail Distillery in Danville, Ky. — 12,500 barrels — was already promised to an outfit called Washtucky Holdings, according to a lawsuit filed in federal court in Louisville earlier this month.

Washtucky is linked to a hedge fund managed by a Seattle, Washington investment firm that offers bourbon as an “alternative investment” to its well-heeled clients.

Without needing to set foot in Kentucky, these investors are betting that the bourbon boom will keep booming, meaning whiskey barrels will continue to appreciate, providing a significant return for those who hold onto them a few years before selling.

According to the lawsuit, they lost out on a chance to nearly triple the money they planned to pay for Wilderness Trail's barrels.

Investor interest in bourbon

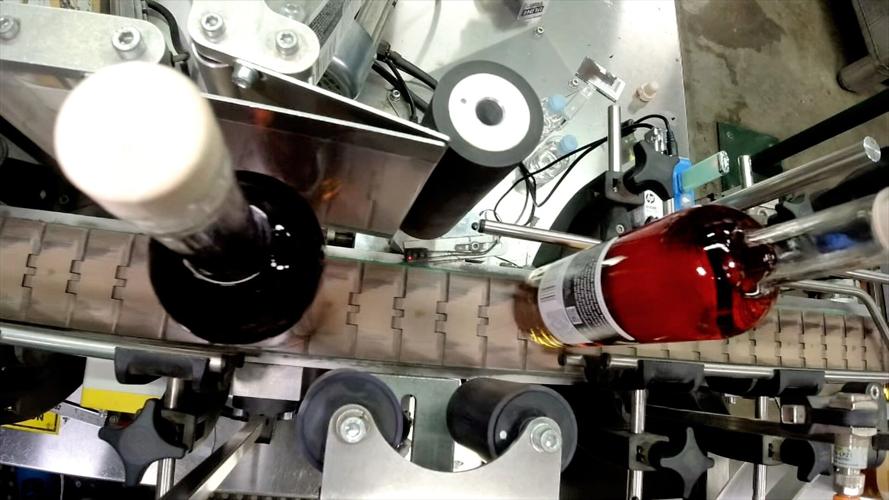

The two-decade resurgence of bourbon has led to a record 11.4 million barrels of the aging whiskey in Kentucky as well as record annual production, according to the Kentucky Distillers Association, the industry’s state trade group.

Meanwhile, distillers — from established giants like Beam Suntory’s Jim Beam and Sazerac’s Buffalo Trace to younger upstarts like Wilderness Trail — have poured billions into increased production and barrel storage.

One indication of all the money sloshing around the industry is the presence of financial firms looking buy up barrels as an investment.

Fred Minnick, author of “Bourbon: The Rise, Fall, and Rebirth of an American Whiskey,” said distilleries have long pledged some or all of their output to other distillers or people who want to sell under their own brands.

“The practice of contract distilling — or buying barrels aging in someone else’s warehouse — is as old as the business has been around,” he said in an interview. “What’s different here is, this is an entity from the financial sector doing something versus another distillery or someone bottling it.”

Washtucky is linked to Freestone Capital Management, a Seattle-based wealth management firm that oversees $8.9 billion in assets, according to a regulatory disclosure filed in November. Freestone provides investment advisory services and manages private funds on behalf of individuals who generally have at least $1 million to invest and institutional clients such as endowments and pension funds.

A small corner of Freestone’s portfolio is the Freestone Bourbon Fund, a hedge fund created in 2019 that has nearly $138 million in assets and 269 investors, according to Freestone’s Form ADV.

Hedge fund strikes bourbon deals

Freestone, acting through its affiliate Washtucky, first struck a deal to buy barrels from Wilderness Trail in February 2020, according to the lawsuit.

The deal followed a tour of the Danville distillery, during which Wilderness Trail co-founder and CEO Shane Baker told Freestone representatives that he had recently sold 600 four-year-old barrels for $2,850 per barrel, according to the complaint.

That day, Freestone’s Washtucky inked a deal to purchase up to 40,000 newly filled barrels from Wildnerness Trail over four years, a haul that was later expanded by up to 13,500 barrels when Wilderness Trail unlocked more capacity, according to the lawsuit.

Washtucky initially agreed to pay $660 per barrel plus storage and transfer fees, rising to as much as $758 per barrel through subsequent agreements, according to documents filed in the lawsuit.

Wilderness Trail produced at least 7,500 barrels for Washtucky, according to the lawsuit.

But the relationship broke down in 2022 when Baker became evasive about when the distillery would churn out the remaining 2,500 barrels it owed Washtucky for the calendar year, culminating in what Washtucky described as Baker’s wrongful termination of the contract by email on Dec. 7, 2022.

Baker cited the “Campari/WTD partnership” announced Oct. 31, 2022 as the reason Wilderness Trail could not continue making barrels for Washtucky, according to the lawsuit.

Campari, which has owned famed Kentucky bourbon brand Wild Turkey and its Lawrenceburg, Ky. distillery since 2009, disclosed in October that it would pay $420 million for a 70% stake in Wilderness Trail, part of plan to buy the entire Danville distillery for $600 million by 2031.

The Milan, Italy-based conglomerate is positioning bourbon to become its “second major leg” spirit category after its aperitifs, Aperol and Campari, according to a press release.

Baker, the Wilderness Trail co-founder, declined to comment on the Washtucky lawsuit.

While not named as a defendant, Campari may have wrongfully interfered with Washtucky's right to receive barrels from Wilderness Trail, according to the lawsuit. Campari did not respond to a request for comment.

Freestone Capital Management executives also did not respond to questions submitted to the firm’s attorney.

Wilderness Trail’s failure to produce the barrels for Washtucky cost Freestone’s bourbon fund about $21.7 million in lost profits before storage and transfer costs, according to the lawsuit.

The calculation is based on the $2,500-per-barrel price Washtucky claims it was receiving on its two-year-old barrels as of December 2022, which implies a roughly 280% return over two years. The lawsuit doesn’t specify if those barrels originated with Wilderness Trail or another distiller.

'Money-people chasing it'

Minnick, the bourbon author, said institutional investments into bourbon are a natural outgrowth of the industry’s rapid expansion over the last two decades.

After equity investors in upstart distilleries like Rabbit Hole and Angel’s Envy made out handsomely when those brands were sold to large companies, people are looking for on-ramps to the industry, he said.

“You have money-people chasing it,” he said.

Contract buyers have always been potential assets to distillers, particularly younger whiskey makers whose products are not as well established, Minnick said. The benefit is guaranteed revenue.

“The distillers actually often will seek this out because it’s an opportunity for them to have cash flow,” he said.

Freestone’s commitment to buy at least $13.2 million of barrels during the first two years of the Washtucky contract “significantly benefitted Wilderness Trail by assuring Wilderness Trail of a market for its bourbon at a guaranteed price,” according to the lawsuit.

Competition for barrels

Jeremy Kasler, shown in March 2021, is the CEO of CaskX, a business that allows retail investors to buy bourbon barrels. WDRB file video

Freestone and its clients are not the only investors looking to obtain bourbon barrels.

Jeremy Kasler is the CEO of CaskX, a company that facilitates retail investors’ purchases and sales of bourbon and scotch barrels. Previously, it was only brokers or distillery-industry insiders who could invest in barrels, he said.

CaskX investors in the United States must be “accredited,” meaning they have a high income or net worth.

Since CaskX started offering bourbon investments in 2021, the competition to acquire barrels has grown fiercer, Kasler said.

“When we first started negotiating with the distilleries, the opportunities were much, much greater. Most of the people we were speaking to could offer us something,” he said. “And now more and more … they’re telling us they’re having conversations with fund managers (or) family offices.”

Kasler said the involvement of institutional investors in the market shows that sophisticated professionals see opportunities in bourbon.

“These people who spend a lot of time researching (and) doing due diligence, they see bourbon barrels as a good investment,” he said.