Vibrant Lights, Minor Disruptions

On November 11, 2025, people across the United States looked up in awe. The northern lights, usually reserved for places like Canada and Alaska, were instead visible as far south as Alabama and Florida. The vibrant display of auroras was caused by a strong geomagnetic storm, the result of a burst of solar activity that sent charged particles racing toward Earth hours earlier.

The geostorm caused only minor disruptions, such as a 30-minute blackout of high-frequency radio transmissions across Europe, Africa, and Asia, as well as delaying the launch of NASA’s ESCAPADE satellite. However, it did serve as a reminder that the Sun is still currently in an active phase, and with that comes an increased potential for “space weather” events that can affect the technologies on Earth that we rely on every day.

Understanding Geomagnetic Storms

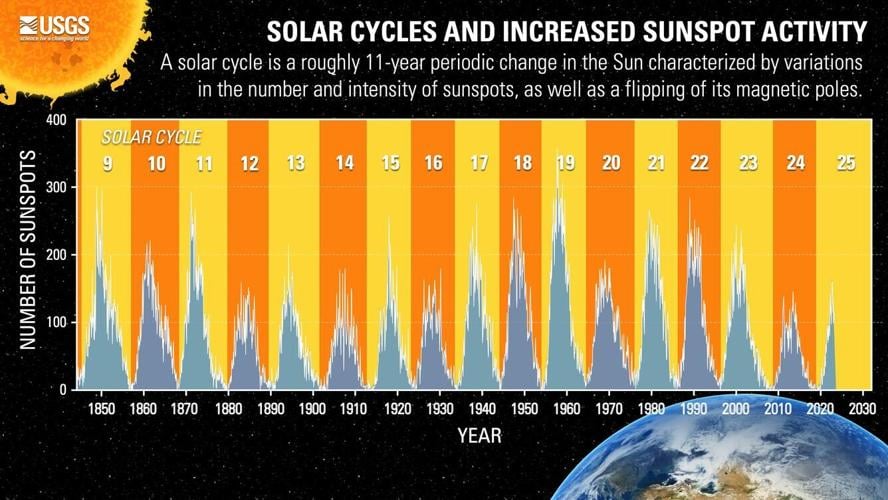

The Sun follows an approximately 11-year cycle of magnetic activity. As it passes through the peak of Solar Cycle 25 and enters the early declining phase of the cycle, increased activity continues to produce more sunspots, solar flares, and coronal mass ejections. These solar eruptions can send massive waves of energy into space. If one of these eruptions is directed toward Earth, it can disturb our planet’s magnetic field and trigger a geomagnetic storm. Other recent notable events occurred in May 2024, January 2025, and June 2025.

Although these geostorms have occurred throughout history, their potential impacts to modern society have grown as our dependence on technology has increased. Today, geomagnetic storms can interfere with satellite operations, disrupt GPS and radio communications, and in more extreme cases, adversely affect electric-power transmission systems and lead to widespread blackouts.

A solar cycle is a roughly 11-year periodic change in the Sun characterized by variations in the number and intensity of sunspots, as well as a flipping of its magnetic poles.

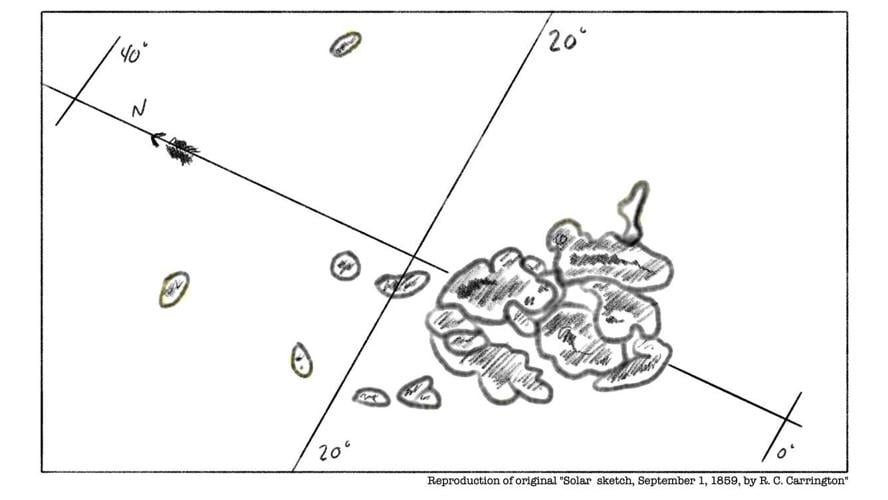

One of the most well-known examples of an extreme geomagnetic storm is the “Carrington Event” of 1859. Named after British astronomer Richard Carrington, who observed the solar flare that preceded it, the geostorm caused widespread disruption to telegraph systems, which were the backbone of global communication at the time. Operators reported sparks, fires, and electric shocks.

If an event of that magnitude occurred today, the consequences could be far more significant. Modern infrastructure, including satellites, navigation systems, and electrical grids, is far more powerful, complex, and interconnected than it was in the 19th century. One failure could have a cascading effect across many of these networks. Automated electronic functions could falter. Blackouts could affect not just neighborhoods, but entire regions. Flights at multiple airports could be delayed or cancelled. And although these disruptions may only last for a few seconds, in a worst-case scenario, they could go on for days or weeks.

Northern Lights (Aurora borealis) and outdoor electrical switchgear at winter night, snow field

Northern Lights (Aurora borealis) and outdoor electrical switchgear at winter night, snow field.