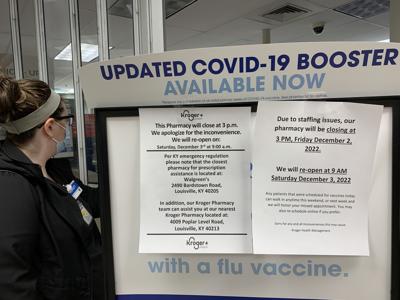

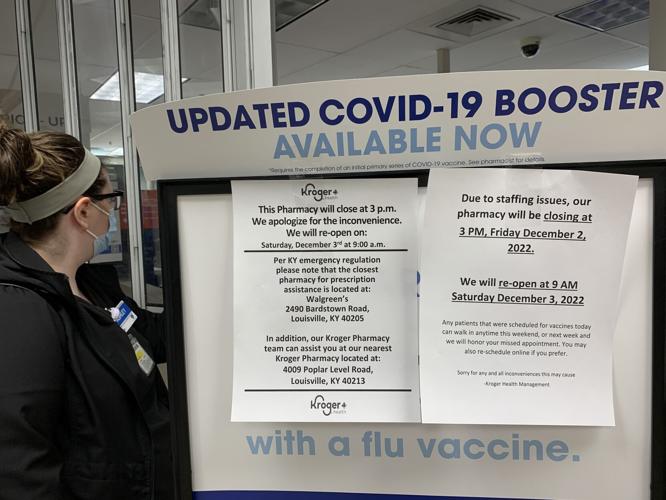

LOUISVILLE, Ky. (WDRB) -- One Friday earlier this month, customers at the Highlands Kroger store on Bardstown Road watched employees roll out the folding doors to the in-grocery pharmacy at 3 pm. Prescriptions could not be filled until the following day at 9 a.m., according to a sign explaining the early closure.

Pharmacy clerks told frustrated customers the problem: There was no pharmacist available to work, forcing the store to close early because regulations require a pharmacist to be present. The grocery chain's pharmacists are already working a lot of overtime, they said.

Kroger did not respond to a request for comment, but the incident isn't surprising to people familiar with the pharmacy industry.

The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated a nationwide shortage of pharmacists, particularly those working for high-volume retail chains like CVS, Walgreens and Kroger.

"COVID had a huge strain on the health care system as a whole. Pharmacy was not spared from that," said Ben Mudd, a pharmacist and executive director of the Kentucky Pharmacists Association.

During the pandemic, retail pharmacists took on additional work including administering vaccines, and many chose to retire earlier than planned, Mudd said.

The pharmacists' national trade group last year complained of widespread "burnout" among its members. Chains have offered big bonuses to lure pharmacists and are investing in automation to reduce their workload.

In the greater Louisville area, the shortage may be even more acute because pharmacists have options for employment at several e-commerce facilities lured here to take advantage of proximity to UPS' global air hub, Mudd said.

Examples include Chewy, the online pet products retailer, and Rx Crossroads by McKesson.

"We've seen a shift where people are leaving maybe the community pharmacy setting and going to work for either a mail-order pharmacy, of which there are several here in Louisville, or they go work in the health system," Mudd said.

Sondra Tapper-Williams, a Louisville pharmacist who until last year worked in retail settings for two big chains, is one of those who found a different path. She now works at home helping obtain patient prior-authorizations and part-time for a hospital system.

When she worked in stores, Tapper-Williams said shifts could run as long as 14 hours with no breaks, and the pace was frantic.

"There would be times I'd be there with one technician — sometimes no technician — and the drive-through is going off, people are coming in to the front counter, the phone's ringing, you got electronic prescriptions coming in, and you're having to process all of that," said Tapper-Williams, who requested that her employers not be identified publicly. "It was a lot to deal with."

It's now more common for retail pharmacies to close briefly for staff breaks, Tapper-Williams said, but for many pharmacists, that relief "might have been a little too late" coming.

Data show fewer people are interested in entering the profession.

The number of applicants to U.S. pharmacy schools has steadily declined since a 2012-2013 peak of 17,617, according to the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. In 2020-2021, 13,324 people applied to pharmacy schools, about a third fewer than a decade ago.

At the Sullivan University College of Pharmacy — the only pharmacy school in Louisville — enrollment peaked at 110 students in 2017, according to dean Misty Stutz. This year's class, which began in July, has only 31 students, which is not enough for the school to be "sustainable" in the long run, she said.

A doctorate of pharmacy requires perquisite college courses in scientific subjects as well a graduate program that takes three or four years to complete. Sullivan estimates its total sticker price at about $162,000.

Pharmacists in the Louisville-Southern Indiana metro area earn $123,880 a year on average, more than twice the pay of the average job in the area, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

But high wages often cannot compensate for frantic working conditions caused by a revenue model that relies on dispensing high volumes of prescriptions and leaves little time to counsel patients or provide more holistic care, according to Mudd and Stutz.

"Oftentimes, when you go into some of the retail-community pharmacies, you'll see a pharmacist only checking prescriptions and that's all they do all day," Stutz said. "And that is not what they were trying to do (as a pharmacist) and they're not really satisfied doing just that."

The complexity of how pharmacies — and in turn, pharmacists — are paid plays a big role in the working conditions, Mudd said. He blamed pharmacy benefit managers, the companies that serve as middlemen between drug manufacturers and health insurers.

"In any other industry, really, if this shortage occurs, the market would say, 'Well, just pay your people more money, and they will come … you'll hire these positions.' But pharmacy is so specific because there are three pharmacy benefit managers that really dictate — they set the how much you're going to get reimbursed for that one claim or whatever the case may be. And we haven't seen a huge increase in how much they're paying."

Even large companies like Kroger, which operates more than 2,000 pharmacies, are unable to better staff pharmacies because of the pricing model, Mudd said. He pointed to Kroger's contract fight with Express Scripts, one of the big pharmacy benefit managers. Kroger is leaving Express Scripts' network on Jan. 1 after claiming the pharmacy benefit manager pays below the company's cost of operating.

The Pharmaceutical Care Management Association, the Washington, D.C. trade group that represents pharmacy benefit managers, says so-called PBMs reduce drug costs for patients and their insurance plans by an average of $962 per person annually.

A spokesperson for the PCMA pointed to an analysis claiming that there are 70 PBMs and that the industry is "highly competitive."

Stutz said Sullivan is working on ways to increase applications to its pharmacy school, including establishing feeder undergraduate paths at the University of Louisville and Indiana University Southeast.

In 2021, Kentucky lawmakers unanimously passed a bill that requires commercial health plans to reimburse pharmacists for services, such as testing and treating for the flu or providing tobacco cessation, in addition to payments for drugs dispensed.

The bill has been slow to implement, however. Mudd said to his knowledge, the only insurer to allow reimbursements for those services so far is Anthem, which begins Jan. 1.

"We're still working out the kinks for that," Stutz said. "But that's also a very positive (development) because it allows us time away from the product to actually spend with you and work on your medication optimization, and then (to) get paid for that time."

Tapper-Williams, who graduated from Sullivan in 2013, said people interested in becoming pharmacists should be aware that there are good opportunities in clinical and research settings, though competition for those jobs can be high.

"There's a lot of different options out there. It's not all just retail. You just have to find those other gems," she said.